BROKEN LIVES || In God We Trust

Story Published on October 31, 2010

Some still seek cure at old Cafaro hospital

By DOUG LIVINGSTON

TheNewsOutlet.org

Cafaro Memorial Hospital on Youngstown’s North Side was, for decades, a place where the sick went to be cured.

Though it closed in 2000, curing the sick continues there. They are men, broken and in disrepair — a living version of the hospital’s bleak neighborhood near Wick Park. Buried behind arm-length tattoos and weathered smiles are troubled lives scarred by drug and alcohol addiction.

Inside the worn 1953 hospital, 48 beds are continuously filled with often desperate and often despised souls. Greg Todd grew up in East Liverpool. He became an addict first, then a thief, and finally a convict.

Bob Pavlich awakes every morning in a body ravaged by years of cocaine addiction. And And Anthony Sanders’ cold, blue eyes stare through you as he recalls one crime-and drug-filled night. Calmly, he admits, “That’s one night I should have died.”

From Boardman, Columbiana, Howland, New Castle, Youngstown and elsewhere they come. Their families won’t have them. Prison could worsen them — or kill them. In between prison and death sits the Ohio Valley Teen Challenge rehabilitation center, an ill-fitting name as all of its residents are adult males, mostly in their 20s and 30s — but others in their 40s, 50s and even 70s.

Teen Challenge USA has been rebuilding lives since 1958. It is a network of 242 residential centers across America and more than 1,000 worldwide. The centers deal specifically with men, women and youths who are suffering from addiction or its consequences. In March 2009, Teen Challenge opened a residential center in Cafaro, later known as Youngstown Osteopathic Hospital, on Florencedale Avenue.

“We’re here to bring life to men who have given up on life,” said Roy Barnett, OVTC executive director. “We rebuild people — restoring families and reclaiming a community.” Men pay a one-time $1,000 fee to enter the live-in treatment program that will take over their lives for the next 12 months. Depending on the time of day, the facility is part monastery, part fraternity and part military barracks.

While it’s fraternal in many ways, it’s imprisoning in others: No unescorted leaves off building grounds, visitors-only on Saturdays, set bedtime, set wake-up time, no fighting, cursing, tobacco or alcohol, and no exceptions. Punishment is often expulsion.

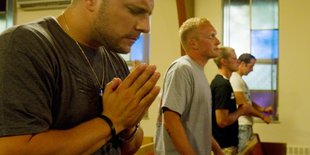

And OVTC’s single-most employed rule is also its most dividing: God.

Unlike other rehab programs, OVTC uses Scripture instead of prescriptions. The Bible, and God, are everywhere — in chapel, at dinner, on the job, and often, spontaneously in the hallways. Mostly the men pray for change. They ask for freedom from the shackles of addiction.

“I tried for so long to change my heart,” Boardman resident and OVTC graduate John Kelly said. “He [God] changed my heart.”

The men are taught morality and dignity. An expansive work program on- and off-site is designed to develop a strong work ethic while also paying the facility’s bills. They learn how to be human again. “What we’re instilling in them is just good old-fashioned values,” said Administrator Cathy Barnett, who is married to Roy.

“An addict is a very selfish person. Teaching them to go to work every day takes the focus off them,” she said. Mahoning County’s crime and drug use put the city in dire need of a center to take in these men who are too old for the juvenile system and a regretful burden on their families, Roy Barnett said.

For 20 years, Youngstown’s own had been sent to Teen Challenge centers across America. Now, men from the Mahoning Valley and across the nation come here to the North Side facility.

But OVTC success — if measured by graduates — has been limited.

In its 19-month existence, just 11 men have graduated even though 166 men have enrolled. In all, 100 men have failed to graduate.

Some men are thrown out for violations or violence. Others walk out on their own accord for a variety of reasons. “Not everybody’s going to stay in Teen Challenge,” Roy Barnett said. While it’s always full, it’s a revolving door of new faces every day. As one man exits, another is admitted.

Amid this seemingly chaotic life, OVTC has its community supporters, from judges to other addiction-support agencies to facilities that employ the men, such as the Canfield Fair or the Covelli Centre. OVTC operates on an annual budget of $390,000. The nonrefundable $1,000 entrance fee is a small portion of revenue and equates to less than $3 a day for room and board.

Hence the residents are the labor. Earnings from the various jobs go directly toward maintaining the facility and work programs. You will find OVTC men landscaping blighted properties in Youngstown. You’ll find them working security at Pittsburgh Steelers games. They cater lunches. They clean up the Covelli after events.

Inside the facility, the men live together on donated bunk beds. They work together and play together. They cook and eat their meals together. It is a daily struggle of egos and addictions.

OVTC is staffed 24/7 by 15 staff members, including the Barnetts. Ten staffers are like Al Franco — graduates of the program from this facility or others in the U.S. Franco grew up in Trumbull County and in a church-going family. “I liked drugs and alcohol better,” Franco said. A 1985 graduate of Mathews High School, Franco recalls smoking $700 to $1,000 of crack cocaine each day. He said he often purchased crack from the North Side houses that now surround OVTC. The drugs he bought he often pushed to friends in Champion.

Today, Franco pushes boxed lunches instead. He is the head chef at the center and runs its Hope Catering Service, one of OVTC’s many work programs.

The sustainability of OVTC depends on the success of the numerous fundraisers, jobs and donations collected. But, ultimately, the program depends on the very men who depend on it. There are no bars or locks holding them, just a desire to get better. As they toil for the program, they watch as others leave, only to crawl back after relapsing.

Some of the men who quit find difficulty in dealing with the religious aspect. Although they initially accepted it, they soon learn that

Christianity saturates the entire program, and it prompts them to leave. Other men take offense to the overwhelming joy of the more tenured residents.

“Everybody was too happy,” said Sanders, 23, of Warren. His first time in OVTC, Sanders quit the program because he could not quit his prescription medication. Less than 30 days later, he came back begging for help.

“That’s where that whole submission thing comes in,” Sanders said. “Giving it over to God ...”

This story continues tomorrow in The Vindicator and on Vindy.com.

The NewsOutlet is a joint media venture by student and professional journalists and is a collaboration of Youngstown State University, WYSU radio and The Vindicator.

Subscribe Today

Sign up for our email newsletter to receive daily news.

Want more? Click here to subscribe to either the Print or Digital Editions.

AP News