‘Great’ 1919 strike forged long-term gains for labor

By WILLIAM K. ALCORN

alcorn@vindy.com

YOUNGSTOWN

Labor Day 100 years ago was not just a time to sit around the backyard with family and friends and have a picnic and drink a few beers.

Rather, it was the year of the Great Steel Strike of 1919 and labor unrest in general, particularly in the Mahoning Valley. It was perhaps fermented by World War I, in which the United States participated from April 6, 1917, until Nov. 11, 1918.

During the war, wages and working conditions improved in order to support the war effort. But soldiers came home to find the improvements did not last and inflation after the war made it even more difficult to afford basic needs.

Also, Labor Day was a relatively new event.

The first Labor Day was Sept. 5, 1882, a Tuesday, in New York City. Residents celebrated with a picnic, concert and speeches, and 10,000 workers marched in a parade from city hall to Union Square. President Grover Cleveland declared Labor Day a national holiday in 1894.

But a century ago, according to headlines compiled from The Vindicator by the Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County, labor unrest was rampant.

A massive strike in 1919 was the largest individual example of worker dissatisfaction during that period.

According to Ohio History Central, in 1919 workers represented by the American Federation of Labor went on strike against United States Steel Co., and were joined by workers at other companies.

Because the strike eventually involved more than 350,000 workers, it became known as the Great Steel Strike of 1919.

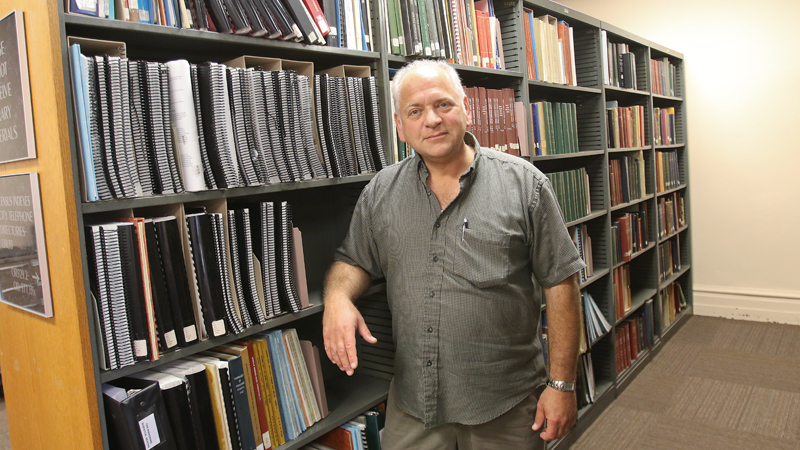

It’s an interesting episode in Youngstown’s history, explained Timothy A. Seman, genealogy and local history librarian at the Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County. Many families owe their presence in the Mahoning Valley to the immigration and migration flows that answered industry’s call before, during and after World War I.

“If there is one instructional characteristic of this era for our own time, it is the way in which myopic forces for the status quo time and again use what are largely irrelevant labels of identity to defeat working-class interests or the common pursuit of happiness.

“Our headlines today demonstrate our lack of unity and the inability to identify and work toward the public good. As we picnic this Labor Day holiday, we should contemplate the struggles of our ancestors, and look beyond our own fences,” Seman said.

Although the Great Strike of 1919 ended in defeat for the workers, it eventually led to public awareness of the “horrid” working conditions of steel workers. In the next two decades, movement was made toward an eight-hour day and five-day work week, Seman said.

The Great Strike of 1919, and all the smaller strikes of that era, added to the gradual movement toward collective bargaining, demonstrating the connection between it and the Little Steel Strike of 1937 of which the Mahoning Valley, home to Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. and Republic Steel at the time, was the epicenter.

MAJOR STRIKE HEADLINES

Vindicator headlines revealed issues that were being contested and the myriad groups besides steelworkers that conducted strikes, including telephone operators, barbers, bakers, telephone linemen and plumbers.

The headlines also chronicle some of the problems on both sides of the picket lines in 1919. Here are some examples:

“AFL enrolls 12,000 members,” June 5.

“Government conciliator named in Ohio Leather Strike,” Aug. 27.

“100 men deputized for special strike duty,” Sept. 22.

“Strikes quiet here, rioting in Farrell, Pa.; embargoes placed on materials for plants,” Sept. 23.

“Manufacture of near beer banned during strike,” Sept. 25.

“Workers beaten, seven pickets held; Ohio Leather strike ends,” Oct. 1.

“Trumbull Steel men return; one killed, two hurt, five arrested in melee at the Hubbard Sheet & Tube plant,” Oct. 9.

“Plants attempt operations; Sheet & Tube storekeeper beaten,” Oct. 13.

“Serious rioting at Steelton and Poland Ave.,” Oct. 22.

“Union distributes food; women rioters arrested,” Nov. 4.

“Republic men ask protection against pickets; citizens organize against terrorism,” Nov. 2.

“Trouble at all plants,” Nov. 7.

“Man beaten by strikers, dies,” Dec. 17.

According to Ohio History Central, the Great Steel Strike of 1919 was a failure for steelworkers.

“Company owners portrayed the workers as dangerous radicals who threatened the American way of life, preying on many American fears of Communism during that era. Because many of the striking workers were recent immigrants, owners were able to portray them as instigators of trouble,” according to OHC.

“Government officials used National Guard and federal troops to put down the strike in many cities, leading to violence and even worker deaths in some cases.”

The Interchurch World Movement (January 1919 to April 1921) offered another perspective on the Great Steel Strike of 1919 in its World Survey Conference of January 1920. The movement’s report was sympathetic toward the steelworkers, who struck for a reduction of the 12-hour day and seven-day week work schedules and safer working conditions.

The report countered pro-management, anti-union propaganda and helped move public opinion and government toward mandating the now-standard eight-hour workday.

Seman added some of his vast knowledge of local history to the story.

RACE, CLASS PROBLEMS

Seman said he learned from the 1920 U.S. Federal Census there was a Sheet & Tube labor camp in Coitsville that housed about 550 workers – 250 white (East European) and 300 black and Mexican.

“It indicates that if these men were used as strikebreakers, then there is no support for the monolithic point of view that only blacks were used as potential strike breakers,” he said.

Also, said Seman, the OHC’s summary of the Great Strike of 1919 illustrates companies used multiple scare tactics and acts of oppression, including threats of violence, threats of termination, and rallying public paranoia toward ‘radical’ elements, i.e., a communist conspiracy.”

Moreover, said Seman, while factory owners and management practiced a cohesive strategy of exploiting divisions among the working class, the internal dynamics of steel mill culture among workers displayed anything but unity of purpose and facilitated this exploitation.

Old immigrants or those born in the U.S. tended to hold favored skilled positions in the mills and were less likely to support the strike in fear of being unfastened from their roles. There was tension between them and the new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, who comprised most of the unskilled laborers and who favored unionization of the industry.

These men, many unnaturalized aliens, sought a permanent home in the U.S. due to the mobilization for war, changed post-war conditions in Europe, the rise of nationalism, and their place in securing victory. These workers sought a greater voice in determining working conditions, wages, and upward movement in the mills, Seman said.

African-Americans were treated in accord to their low social and economic status. Some black workers were already employed as mill laborers, some were recruited by industry to meet labor demands before the strike, and others were used as strikebreakers, he said.

When striking became identified with disloyalty to the United States, American-born steelworkers in particular felt pressure to cross picket lines. The steel strike deepened divisions among the race and nationality groups in the industry.

In any case, African-Americans were instruments for industry ends and were less likely to support a strike that would give rise to a union in which they would be denied membership. Jobs were needed, even the 12-hour day, seven-day week variety, Seman said.

“We have then three general interest groups within the working class, divisions that helped to erode the foundation of the strike effort and ended any hope of achieving the goals of the strike. In all, racism, ethnocentrism, and fear mongering would be used to sow division and exploit fault lines,” he said.

43

43