Domestic violence cases at YSU, OSU share similarities

By AMANDA TONOLI

and JUSTIN WIER

news@vindy.com

YOUNGSTOWN

YSU Report

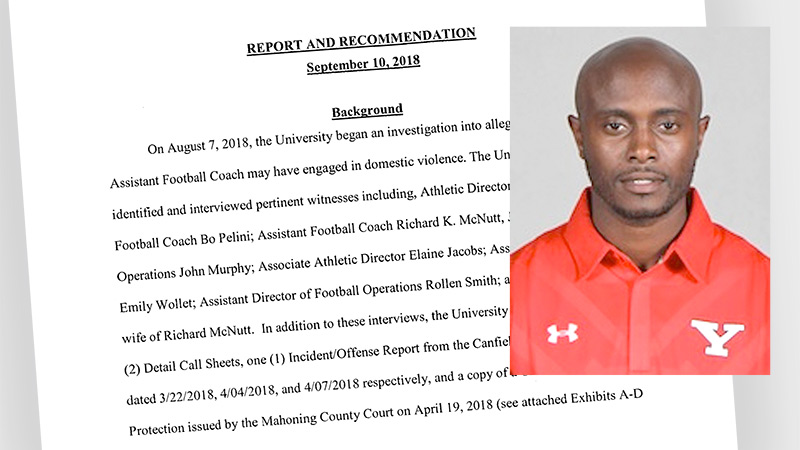

Richard McNutt, a Youngstown State University assistant football coach, violated no university policy after allegedly engaging in a domestic violence incident in April, a report from the university concludes.

Youngstown State University officials claimed they received reports of an assistant

football coach’s involvement in a domestic-violence incident in April.

Yet, the university took no action until Aug. 7, six days after the start of a media frenzy around similar allegations at Ohio State University.

A Sept. 10 YSU report recommended Richard McNutt receive a five-day suspension for an incident in which he

allegedly pushed his wife and knocked a phone out of her hand during a marital dispute April 7.

YSU President Jim Tressel, who the report said was aware of McNutt’s marital issues, declined to comment on the delay in action declaring it a personnel matter.

“[The OSU case] probably influenced our campus to look at our policies,” Athletic Director Ron Strollo said. “Anytime something like this happens, it gives you a time to pause and take a closer look at what you’re doing and try to get better.”

Other senior administration officials contacted by The Vindicator declined to comment on the timing of the investigation and whether the OSU investigation prompted action at YSU.

Shannon Tirone, associate vice president for university relations, pointed Vindicator reporters to the report.

“You know what we know,” Tirone said.

University spokeswoman Becky Rose said YSU is reviewing its policies on domestic violence.

“What came out of that report was that we need to review our policies and come more in line with what’s going on in the world

today,” she said. “So that’s happening.”

THE TIME LINE

A time line assembled through the inspection of police, court and university records shows a number of events involving McNutt between Feb. 22 and April 19 that resulted in three calls to police, one police report, a mutual restraining order and a protection order issued against him.

McNutt’s wife filed for divorce Feb. 22. He was served with the notice of divorce and a mutual restraining order while at work at Stambaugh Stadium the next day.

Without referencing the February filing, the Sept. 10 report says: “The facts establish that the incident which occurred on April 7 was the only incident that potentially required reporting.”

Thus far the university has made no comment on whether being served with divorce papers and a restraining order on school property require a report to superiors or those in charge of campus security.

A university policy states any student or employee who has obtained a protection order must inform their immediate supervisor and the university police department and provide the police department a copy.

YSU police Chief Shawn Varso said the department never received the order of protection filed April 19 against McNutt.

“In this case, for some reason, we didn’t get one,” Varso said.

The university report said McNutt self-reported the April 7 incident to football coach Bo Pelini who in turn told athletic director Ron Strollo in April “around the same time the incident occurred.”

The YSU report does not provide many specific dates and uses terms such as “generally informed” to describe supervisors’ knowledge of McNutt’s ongoing marital issues.

But after the April report, nothing happened until August shortly after media reports on OSU football coach Urban Meyer having knowledge of a 2015 domestic violence incident involving his assistant coach Zach Smith.

The case commanded national media attention for the week leading up to the start of YSU’s investigation.

OSU PARALLELS

Cryshanna Leftwich-Jackson, former women and gender studies program director and acting chairwoman of politics and international relations at YSU, said when she heard about the case, she immediately thought of the Urban Meyer case.

“Once again we have this culture of bad behavior,” she said.

Though the YSU case has several parallels to the OSU case, the OSU case resulted in suspensions for Meyer and athletic director Gene Smith for their failure to alert the compliance office.

Meyer and Gene Smith relied upon the fact that Zach Smith had not been arrested or charged in a 2015 incident.

Similarly, the report issued by YSU states “no further steps were taken in reliance upon the fact that law enforcement made no arrest nor brought criminal charges against Mr. McNutt.”

The YSU report does allow that because of the victims’ reluctance to pursue charges in domestic violence cases “those indicators should not be the deciding factors for determining when to take action and what action to take.”

LARGER IMPLICATIONS

The McNutt case also shows how the handling of domestic-violence cases can put victims in a difficult situation.

According to Canfield police records, an assistant Mahoning County prosecutor authorized a domestic-violence charge against McNutt but was advised not to pursue it once McNutt’s wife decided not to press charges.

She told a detective she “was made aware that McNutt would be fired from his job if criminally charged and that would risk her children not having health care and additional benefits.”

McNutt’s wife declined to speak to The Vindicator or who made her aware of potential implications of pressing charges.

Leftwich-Jackson said people are put in situations where they tolerate behaviors like domestic violence.

“Say he loses his job and he’s the sole breadwinner – is there [enough] support in this community and at this university for a spouse who has been the victim of domestic violence?” she asked. “There’s no cookie-cutter policy, but there are always ripple effects.”

Malinda Gavins, program director at Sojourner House, agreed, saying survivors of domestic violence often stay in dangerous situations because of family concerns.

BACK TO OSU

Family and financial concerns also played a role in the decision-making process at OSU.

Meyer told an ESPN reporter last week about the Smith case: “My intent was to try to help all involved. ... I had two choices, fire a man and really put a family in upheaval financially et cetera, or try to stabilize someone so he can go off and be a good father.”

Survivors of domestic violence struggle with these decisions. The average woman in an abusive relationship will leave that relationship seven times before she leaves for good, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Gavins said the solution is better education.

“We need to put out information and make it available to the community, and make sure there are resources,” Gavins said. “There are services out there.”

Amanda Fehlbaum, acting director of the women and gender studies program at YSU, agreed society needs to draw attention to the resources available to survivors and their family members.

“We don’t have a society set up as a system to say you’re going to be OK on your own,” Fehlbaum said. “It would be a bunch of hoops to jump through that some people aren’t ready and able to do at the spur of the moment.”

A MILITARY SOLUTION?

The U.S. military has a program that provides benefits to children and spouses who suffered abuse at the hands of a service-member for one to three years.

It applies to the families of those who received a court martial for abuse.

The benefits are the same as those provided to families who lose someone in combat, which currently consists of a basic monthly payment of $1,283 with an additional $317 for each dependent child.

YSU officials did not specify how its domestic-violence policies may change upon review.

Conclusions and recommendations in the report suggest it may reduce its threshold for taking action in domestic-violence cases.

University spokesman Ron Cole emphasized a review of policies will clarify reporting requirements and review training regarding workplace and domestic violence.

“If we don’t want our employees to suffer from domestic violence, then we certainly do not want them to engage in it,” the report states.

Survivors of domestic violence can call the Sojourner House hot line at 401-765-3232 or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.

43

43