Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport experiences turbulence

RELATED: Air Force commander counting on continued stability from its "twin"

By JORDYN GRZELEWSKI

jgrzelewski@vindy.com

VIENNA

Over the last 20 years, flights at the Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport have dropped about 70 percent.

And perhaps most significantly to the Mahoning and Trumbull county residents whose tax dollars help support the facility, the airport does not offer commercial flights at this time. Its last remaining commercial airline, Allegiant Air, pulled out of the airport in January. Commercial service has not been available since.

If the status quo holds, this drop in activity could put the airport at risk of losing a significant portion of its federal funding. The airport’s primary funding sources are the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and local taxes.

Passengers must board planes at the facility at least 10,000 times per year to receive a guarantee of about $1 million per year from the FAA. Separately, the FAA provides funding for airport projects that varies from year to year.

Another significant source of funding is a hotel bed tax from Mahoning and Trumbull counties. The Western Reserve Port Authority, the quasi-governmental agency that operates the airport, receives more than $1.5 million annually from that tax, and in the past has diverted a significant chunk to the airport. In 2016, the airport received $1.25 million in bed tax funds.

Port authority officials say the loss of commercial service is a bump in the road and note the airport’s other activity, such as charter, private and cargo flights. They also point to its significance to the Youngstown Air Reserve Station.

They have said they are committed to bringing commercial service back.

“We are absolutely in conversations with other airlines on this issue. It’s an important one, and we realize that,” said John Moliterno, WRPA executive director and interim aviation director.

He said a proposal from an airline could be presented to the port authority board as early as this week.

As the port authority considers future flight options for the airport, it’s worth examining the headwinds that landed the airport where it is now and what its prospects are for the future.

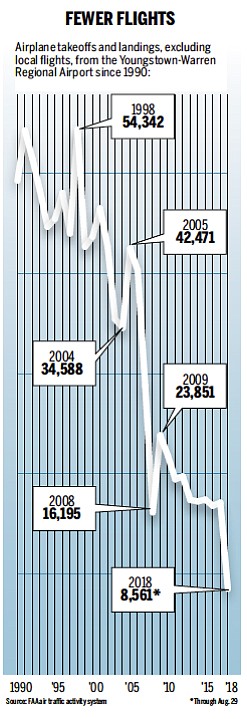

FEWER FLIGHTS

In 1990, about 49,000 flights took off and landed at the airport, according to FAA data. A high point came in 1998, with about 54,000. The flights dropped from there, with about 42,000 reported in 2005; fewer than 22,000 in 2010; about 17,500 in 2015. Last year about 17,000 flights took off and landed at the airport, and so far this year about 8,500 have.

Those figures represent all nonlocal flights. The airport also has local takeoffs and landings – meaning the planes remain near the airport for the duration of the flight – that were not i ncluded in this story.

Although commercial service is just one of several types of flights at the airport, those flights play a significant role in determining how much FAA money the airport receives.

The FAA counts enplanements – the number of passengers boarding flights at the facility – in determining how to classify an airport, and thus how much funding to give.

Those numbers have dropped, too. Every year since 2007, the Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport has had more than 10,000 enplanements – the number at which the FAA considers a facility to be a “primary” airport. Primary airports are eligible to receive a minimum of $1 million annually in entitlement funds from the FAA.

The airport hovered near that number in 2007, 2008 and 2009. The numbers climbed over the next several years, reaching about 63,000 enplanements in 2015, according to U.S. Department of Transportation data.

In 2016, that number dropped to about 50,000; in 2017, to about 33,500. While the 2018 figures remain uncertain, WRPA officials acknowledge reaching 10,000 could be a challenge this year.

“Are we near the 10,000 [enplanements] now? No,” Moliterno said. But, “We may get to that number just as we’re operating today.”

If not, the airport is not immediately at risk of losing federal funding. The FAA looks back two years – so, if the airport doesn’t get to 10,000 enplanements this year, the earliest that would matter is 2020. Even then, the agency would not just pull all the airport’s funding.

“It doesn’t mean it’s automatic. We look at everything on a case-by-case basis,” said Tony Molinaro, FAA spokesman for the Great Lakes region. Even if an airport drops below 10,000 enplanements, the FAA will look at what is being done to get the numbers back up.

“That two years is important because it might be just a bump in the road for an airport,” Molinaro said. “It allows for these small bumps. It gives them an opportunity.”

The airport would still be eligible for some FAA entitlement funding, as well as FAA discretionary funding.

For example, the airport receives funding through FAA’s Airport Improvement Program (AIP), which provides grants to airports for planning and development projects.

MARKET CHALLENGES

The airport is far from alone in the challenges it is facing in attracting viable commercial service providers, according to one airline industry analyst.

“It’s true for many smaller airports. As the industry has consolidated in the last 15 years, you’ve seen literally scores of communities lose commercial air service and hundreds no longer have mainline-sized aircraft service,” said analyst Bob Mann.

Mann said the airline industry no longer competes to provide customers with as many route options as possible.

“With industry consolidation, carriers no longer compete on ubiquity. ... Almost 100 percent of their operations are to and from a hub city. They just don’t fly point-to-point services anymore,” he said. “The size of the city they will serve has gotten larger and larger because the size of the aircraft they’re flying has gotten larger.”

That makes it challenging for a smaller market to attract a commercial airline.

Another challenge is that airports are facing increased pressure to provide airlines with incentives.

“It’s a race to the bottom with airlines holding out for larger and larger incentives,” Mann said.

Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport ran into that issue when it paid a revenue guarantee of $361,714 to an airline that briefly offered flights to Chicago in 2016. Litigation following Aerodynamics Inc. ending the service resulted in the WRPA paying $150,000 to the airline.

Mann said one strategy that could work in a smaller market is identifying a destination for which there is high local demand.

“Ultimately, it could be trying to re-attract a regional carrier operating on behalf of a major [carrier] – one of the Delta Connections or United Express or American Eagle carriers,” he said. “Failing that, it’s looking for a smaller operator to fly point-to-point service in meaningful markets.”

That is what the airport is trying to do. Mike Mooney, a partner in Voltaire Consulting who consults for the WRPA, said his focus has been on business-oriented flights.

“We continue to pursue different options to bring a business-travel-oriented air service to Youngstown to major business centers,” he said. “It’s not too hard to figure them out – New York City, Washington-Baltimore, and/or Chicago. It has to be far enough that you wouldn’t drive there.”

Mooney has cited the intense competition in the ultra-low-fare market in the Cleveland-Pittsburgh-Akron “triangle” starting in 2014 as one reason Allegiant ended its Youngstown flights.

By the end of 2015, Frontier Airlines had entered the market and Allegiant had started offering flights out of Akron-Canton and Pittsburgh. Then Spirit Airlines joined the competition.

All that competition changed the triangle from a “backwater to full-scale [ultra-low-cost] battleground,” Mooney said.

Mooney recently said there have been “a few small pull-backs from the intense competition that Allegiant, Frontier and Spirit engaged in in Cleveland and Pittsburgh” since a presentation he gave on the topic in 2017.

But the situation has not changed significantly.

He and airport officials are still targeting the Youngstown-area business community as the best opportunity to provide commercial service.

FUTURE OPTIONS

If things do not work out as planned for the airport, Mann said one of two things could happen. Airports can sit unused or underused for quite a while, as long as they are maintained. In some cases, however, communities with struggling airports have found it more attractive to put the property to a more lucrative use.

“What you see nationwide in smaller airports, even some which are actively used, being valued more for their potential real estate as park land or golf courses, you name it,” he said. “The question is, you reach a decision point where if you head down that reuse path, you’re never going to get an airport back. It’s a terminal decision.”

He added: “You can keep the airport as long as you want as long as you maintain it at a minimal level. At some point, it will require renewal, and it may be there are higher and better uses of the real estate.”

WRPA officials, however, say they are committed to providing commercial service out of the airport.

The board meets Wednesday, at which time there could be discussion of a contract with an airline.

Contributor: Staff reporter Ed Runyan

43

43