Epidemic fatigue fuels calls to end life-saving acts

By JORDYN GRZELEWSKI

jgrzelewski@vindy.com

YOUNGSTOWN

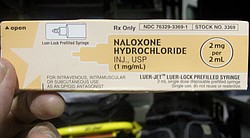

Narcan

Dawn Wrask, a paramedic and clinical coordinator for AMR Ambulance in Youngstown talks about the drug Narcan used to revive overdose victims.

“LET THEM DIE,” ONE PERSON wrote on Vindy.com under a story about Austintown police responding to an overdose in which four doses of naloxone were administered.

“Do we at least charge them for the Narcan? [naloxone]”

“Guess who’s paying for these ‘life saving’ drugs?” wrote a woman commenting on a Huffington Post article about an Ohio sheriff’s refusal to let his deputies carry medication that reverses the effects of opioid overdoses. “The taxpayer, that’s right. Is the life really worth saving?”

“The U.S. needs to ban Narcan,” another person wrote under a Vindy.com story about a fatal drug overdose in the city. “Let everyone know we will not resuscitate anymore overdoses. You overdose you die that is it!”

It’s a sentiment frequently expressedon social media and in real life as the opioid epidemic continues to ravage many communities in the country, including the Mahoning Valley. The epidemic has hit Ohio particularly hard and shows no signs of slowing. The Columbus Dispatch reported that at least 4,149 Ohioans died from unintentional overdoses in 2016, a 36 percent increase from the previous year. Experts believe 2017 will be worse.

Many members of the public are fatigued and frustrated by daily media accounts as the opioid crisis has worsened.

That frustration is evident in Butler County, which made national headlines recently over two controversial stances on the use of naloxone to revive overdose victims.

A city councilman in Middletown proposed that emergency medical responders no longer respond to overdose calls for patients who have already overdosed twice. City officials have since said that the city will not adopt that proposal.

Butler County Sheriff Richard Jones made waves, too, when he said in an interview that he does not allow his deputies to carry naloxone.

“They never carried it,” Jones told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Nor will they. That’s my stance.”

Jones said the policy is based on the cost of naloxone and concern about deputies’ safety.

Some with firsthand experience dealing with addiction and overdoses told The Vindicator they disagree with these stances. All said they understand people’s frustration but do not believe that letting people die from overdoses is the answer. Instead, some said, the root causes of addiction must be addressed, and treatment opportunities must be expanded to get a handle on the country’s worst-ever drug crisis.

Former Youngstown Mayor Pat Ungaro says he understands why people are frustrated about drug overdoses.

In fact, he understands better than anyone. Ungaro’s son Sean died of a drug overdose at age 39. Sean had struggled with addiction for years after being prescribed an opiate pain medication after a hernia surgery. He got hooked on the pills, then eventually turned to heroin.

“No one knows how frustrating it is like a parent,” said Ungaro. “To have a kid, change their diaper, then watch them grow up and die.”

He’s candid on the subject but struggles to talk about his son, choking back tears as he recalls one of their last conversations.

“A day or two before he died, he said, ‘I don’t belong on this earth, but I’m going to leave you my son. That’s the best part of me,’” Ungaro tearfully recalled.

Sean died Oct. 21, 2012.

Ungaro says that people who take a “let them die” stance on addicts are “talking with no emotional involvement. They see it as a nuisance and a cost.”

“I understand their point of view but I don’t agree with them, because a life is precious and we should do everything we can to help a person no matter who they are, as frustrating as it gets, because they can turn it around.”

Ungaro’s other son, Eric, a Poland township trustee who is actively involved in anti-drug efforts in the Mahoning Valley, also expressed frustration with that way of thinking.

“You can’t create a money issue, an $80 issue with a human life,” he said, referring to the cost of naloxone. “The guy who decides who lives, he died on the cross. He’s not some councilman in Middletown.”

He doesn’t believe many first responders have that attitude, noting people he grew up with who went into law enforcement.

“Every one of them, I can say, they signed up to protect and serve. I don’t think they signed up to protect and serve two times, or three times.”

Although naloxone has been in use for decades, it’s only recently become widely carried by law-enforcement officers. New, too, is a law that protects people who call 911 to report drug overdoses. Eric wonders how such developments might have affected his brother.

“Who knows what he’d be doing now?” he said. “There’s so much more hope now.”

For Richie Webber, 25, of Fremont, near Toledo, there is no question how naloxone impacted his life.

After breaking his arm playing football his junior year of high school, Webber was prescribed opiate painkillers. He, too, got hooked and spent several years abusing drugs. He was revived with naloxone three times.

“I’m the third strike. If that policy were to go into effect I’d be dead,” he said of the Middletown proposal.

Now, Webber has been clean for 2.5 years and runs a nonprofit organization dedicated to addiction recovery.

“I know people are just really frustrated, so they’re proposing desperate measures to a desperate problem,” he said.

But, he said, the answer has nothing to do with naloxone.

“This epidemic is never going to change if we don’t offer treatment,” he said. “I think the key thing is teaching people healthy coping mechanisms.”

“I was one of those lost causes,” he added. “If I made it, other people can too.”

SERVE AND PROTECT

Nicole Walmsley, who has been in recovery for 4.5 years and now works with police departments as a treatment coordinator, has vowed to fight against proposals such as the one in Middletown.

This week, she plans to attend a city council meeting to explain to Middletown officials the various ways the city can obtain free naloxone and educate them about the quick-response teams being used in some parts of the state to get overdose victims into treatment as quickly as possible. Walmsley also plans to ask the city to become part of the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative, a national nonprofit group that helps local police departments respond to the opioid epidemic.

“There are solutions all across the state that we are using that are effective,” said Walmsley. “If it’s a matter of, ‘Oh it’s a strain on resources on the city,’ why not reach out for resources?”

Walmsley plans to bring with her a large group of people who also have recovered from addiction, to show city officials “that these are people, and what they can be after they get clean.”

“I fall victim to losing compassion in my line of work,” she acknowledged. “I get frustrated when I’m pleading and begging with an addict to go to treatment, and they do but then they end up relapsing or not completing the program. It’s very frustrating.”

But, she said, it’s another matter to decline to revive someone.

She raised a number of concerns about the Butler County sheriff’s policy, saying she fears that other communities will follow suit.

If so, more people will die, but the problem will remain.

She pointed out that law enforcement sometimes is first on the scene when, for example, a child overdoses on drugs they’ve come into contact with accidentally.

“You want to tell me you’re not going to carry it, and you have a situation where you have the chance to save someone’s life and you don’t? They took a job to serve and protect without prejudice,” she said. “If they can’t serve and protect and save without prejudice, maybe they’re in the wrong profession.”

PRAY FOR COMPASSION

Paramedic Dawn Wrask, clinical manager and education director for American Medical Response in Youngstown and Cleveland, views naloxone as a tool that gives people a chance to live long enough to address their addiction. AMR is the primary ambulance service for the city’s 911 calls.

“We need to see where the problem is occurring. These kids are not going to the streets right away,” she said. “I think we need to get to the root of the problem.”

Wrask said that though the public might be frustrated, she doesn’t sense that feeling among EMS workers.

“Understand, EMS is a calling,” she said. “People don’t get into this field because it’s easy.”

Part of the problem, Wrask believes, is the way naloxone was presented to the public. It restores breathing, but it is not a cure for addiction.

“Narcan was introduced to the public as this drug that could reverse death,” she said. “They do have to understand the limits of Narcan. It is not a miracle. Narcan doesn’t stop the addiction. Narcan brings you back and breathing. The addiction is still there.”

Wrask has been working in the emergency response field since the 1980s. On the many overdose calls to which she’s responded, she is always moved by the family members at the scene who often have no idea their loved one had been abusing drugs.

What she sees is “devastation. Just devastation.

“As a parent, I can’t even imagine,” she said.

The Rev. Lewis Macklin, pastor of Holy Trinity Missionary Baptist Church and a board member for a local drug treatment organization, said he urges people to “pray and seek understanding” if they are unable to summon compassion on this issue.

“I would hope folks would speak with compassion,” he said. “I would hope they would understand that there but for the grace of God, it could be them as well.”

43

43