Ohio EPA effort in 2008 to oversee Warren’s high lead levels fell short

Warren's 2008 Lead Readings

Newly released documents show that Ohio Environmental Protection Agency officials apparently tried to get Warren Water Department officials to come clean with their 47,000 customers in 2008 about problems with the water that caused lead levels to spike, but didn’t follow through.

By Ed Runyan

WARREN

Newly released documents show that Ohio Environmental Protection Agency officials tried to get the Warren Water Department to be transparent with its 47,000 customers in 2008 about the dangers posed by lead in Warren’s drinking water, but the effort fell short.

The city sent a notification to all of its customers, which The Vindicator obtained last month.

The important part of the notice — a chart telling people about the elevated lead levels — was written in scientific jargon most people would not have understood. As a result, almost no one realized the problem existed, including the heads of the city and county health departments.

Equally ineffective was the OEPA order on Dec. 3, 2008, that the water department notify the media about the high lead levels. The water department ignored it.

That decision took away the public’s last line of defense. A Vindicator review of news coverage from that time period shows that neither newspaper covering Warren mentioned the high lead levels, nor apparently did any other media.

The lack of understanding by the public is part of a pattern that has become apparent since lead issues arose in Flint, Mich., last year, in which brain-damaging lead consumption through drinking water has been downplayed by local water officials.

And, state officials charged with making sure local water departments follow the federal and state laws for notifying the public have been shown in recent months to have neglected those duties.

Several state and municipal officials in Ohio and Michigan were charged criminally earlier this year over this lack of adherence to the notification rules.

The Vindicator sought records in March from the Warren Water Department and the Ohio EPA about a problem Warren and state officials discovered in the fall of 2008: Routine testing in Warren and some Howland homes showed alarmingly high lead levels.

The lead readings were high enough to trigger an EPA requirement that the city notify its customers.

Though the notifications told residents how to protect themselves from the dangers of lead consumption, they did not, in plain language, tell customers that Warren had high lead levels.

The notifications also did not explain that this was the first time Warren had lead levels that exceeded the federal allowable level in at least 15 years. They did not further explain that the levels were much higher than in the previous set of tests, in 2005.

WHO KNEW?

Earlier this year, Vindicator reporting uncovered the fact that the city had high lead levels in 2008.

It also revealed that only one city official who would talk to The Vindicator claimed to have known about the problem. Among those interviewed who denied knowing about it are then-Mayor Michael O’Brien, then-Safety Service director Doug Franklin, then-Utilities Director Bob Davis and Deputy Warren Health Commissioner Bob Pinti.

Only Warren Councilman Al Novak claimed to know about it. And he said he had “no comment” when asked why no city official ever brought it up in a public forum or mentioned it so that the public would know.

Warren City Council even authorized a $500,000 engineering study to determine what needed to be done at the water-treatment plant on Elm Road in Bazetta Township to fix the lead problem. All of the council members and other city officials interviewed by The Vindicator denied knowing that one of the purposes for the study was to fix the lead problem.

Earlier Vindicator reporting also revealed that the study was explained to city council members in scientific and vague terminology that hid the purpose of the study.

Federal rules require a water department with a lead exceedance — meaning a high lead reading on routine tap-water testing — to notify all of its customers of the problem. Newly acquired EPA documents show that the agency made sure the notifications went out.

What the OEPA didn’t do was make the city follow regulations that said the city should notify the news media, said Heidi Griesmer, Ohio EPA’s chief spokesperson.

“Warren did not notify the news media,” Griesmer said in an email last week. She said OEPA supervisor Dan Underwood’s Dec. 3, 2008, order to Warren to notify the media was “per Ohio regulations.”

“I cannot speak to why a prior administration took enforcement action or not,” she said of the EPA not taking action as a result of Warren failing to notify news media. The governor of Ohio from 2007 to 2011 was Ted Strickland.

Notification

“However, [current OEPA] Director [Craig] Butler takes notification of the public about lead very seriously,” Griesmer said. “In addition to working with the Legislature to pass HB 512, which requires public water systems to notify residents of lead results much faster than required by the federal rule, Ohio EPA notified public water systems in March that we expect them to send notification and results much earlier than required by federal rule.”

In March, Butler sent Warren and other water departments a letter saying that if they have high lead levels of a certain kind, they must issue a news release within 24 hours. The type of high lead levels Butler was referring to are the type that Warren had in 2008 and Sebring had in 2015.

Gov. John Kasich signed HB 512 a few months ago, and it becomes effective Sept. 8.

The Warren Water Department used its annual four-page Consumer Confidence Report in January 2009 to notify its customers about the high lead. It’s a document Warren Utilities Director Franco Lucarelli didn’t turn over to The Vindicator in March, despite public-records requests. Lucarelli said he didn’t have a copy.

The document, provided last week by Griesmer, reveals one reason why Warren’s water customers were unaware of the high lead levels and why Warren and state officials escaped scrutiny by Warren residents and the media for letting it occur.

The document said a major source of lead in Warren is “corrosion of household plumbing systems.” That is one factor, but EPA documents and the corrosion-control study the city paid for later showed that a more significant reason for the 2008 problem was that the city changed the way it treated the water in 2007.

The change caused water to become more corrosive, thereby removing the protective layer of scale from the inside of water pipes and plumbing. That allowed the water to come in greater contact with the lead in pipes and fixtures and to draw the lead from the pipes into the tap water. Fixing the corrosivity of the water fixed the lead problem.

One city official whose name was on most of the correspondence obtained by The Vindicator in relation to the high lead levels and the changes made to the treatment plant to correct them is Vince Romeo, Warren’s water superintendent.

Romeo has in the past declined to discuss Warren’s high lead levels from 2008. He did not return a phone call for this story. Neither did Lucarelli.

RISKS

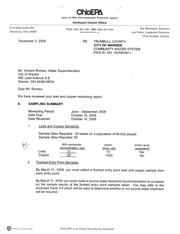

The testing Warren did in the fall of 2008 that exceeded the allowable level set by the federal government came in three sets. In the first set, six of 30 samples were above the allowable level of 15 parts per billion. That was three samples more than allowed. Two more sets of 30 were done, and each had three high samples.

The 12 samples out of 90 that were above the limit gave Warren a lead level of 21 ppb. That triggered the public-notification requirement and the need to study the problem. It’s the same lead level found in Sebring last fall.

Dr. James Enyeart, medical director for the Trumbull County Board of Health, said it would be difficult to say what the negative health consequences would be for a person who consumed water from a water department with a 21-ppb lead level.

There are many variables that would have an effect — whether the consumer had lead service lines or fixtures and how often he or she drank the water, for instance.

What is definite is a blood test that tells someone how many micrograms per deciliter of lead is in their blood. Concern begins when someone has at least 5 mcg/dL in their system, especially children and pregnant women, Enyeart said.

“A goal would be to have a contaminant level of zero,” he said. “There is ample science to prove that IQ and educational level can be affected if the blood level is more than five micrograms per deciliter.”

Enyeart, who was Trumbull County health commissioner until last year, said he was never aware that Warren had high lead levels until he learned about it from news accounts spurred by The Vindicator investigation.

Because of concerns about the health effects of lead, lead-based paint was banned in 1977, and leaded gas was phased out in 1986.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says as a general precaution, it recommends in homes with children or pregnant women with water lead levels exceeding EPA’s action level of 15 parts per billion, “using only bottled water for drinking, cooking, and infant formula.”

Bottled water is regulated federally by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a food product. Instead of accepting EPA’s 15 ppb action level for lead in bottled water, the FDA issued a 5 ppb limit, the CDC says.

SHOULD NOTIFY

In addition to not ensuring Warren notify the news media about the high lead levels in 2008, the OEPA appeared to be reluctant to require Warren to follow other regulations, documents show.

OEPA official Charlotte Hammar of the EPA’s Twinsburg office demonstrated a timid approach to Warren failing to notify its customers of high lead levels on time.

“Technically, Warren needs to conduct [public education] 30 days from notification of the exceedance,” she told the Warren Water Department in a Dec. 22, 2008, memo. Another OEPA document says the deadline for notifying was Nov. 28, 2008. Some notifications went out as late as Jan. 26, 2009, documents say. Warren did not receive a violation for the late notification.

Warren did receive a violation the following year for failing to gather as many samples as required.

Councilman John Brown, who has raised questions in the past as to why almost no water samples have been done in Warren’s low-income Southwest area, said OEPA oversight of Warren’s high lead levels appears to have been too lax in 2008.

“After [Flint,] Michigan, everybody started tightening up the reins,” he said.

QUESTIONS ASKED

The OEPA’s timid oversight of the lead problem appeared to resurface in Sebring in late 2015. Soon after, corrective actions were taken, however.

James V. Bates, the former water-department operator for Sebring, was charged in July with three state crimes, accused of failing to provide timely notice of high lead levels to water customers in Sebring in 2015.

Two OEPA officials, Kenneth Baughman and Julie Spangler, were also fired in February for poor oversight of the Sebring water system.

Baughman’s failure had to do with making sure water-test results were sent from the Columbus office to the Twinsburg office so Twinsburg staff could determine whether the lead-action level was exceeded.

Spangler was fired for not properly managing Baughman and “not providing appropriate corrective counseling or progressive discipline, despite being instructed to do so,” OEPA said.

43

43