Shaun Lane perseveres since losing use of arm in last game

Shaun Lane perseveres since losing use of arm in last game

By Joe Scalzo | scalzo@vindy.com

HILLIARD

Hours before he lost the use of his right arm, before he suffered what Jim Tressel called the second-worst game-day injury of his 37-year coaching career, Shaun Lane woke up in the Fairmont Scottsdale (Ariz.) Princess hotel with an overwhelming feeling of thankfulness.

“Random as it is, I was just thankful for being able to walk and being able to run,” he said. “I don’t know why I even thought that.”

It was Jan. 5, 2009, and Lane was preparing to play the last game of his Ohio State football career, a Fiesta Bowl match-up against Texas at the University of Phoenix Stadium.

Lane was a fifth-year senior, an ex-Hubbard High School star turned backup cornerback/special teams maven who was hoping to play in the NFL, just as his father, Garcia, did in the mid-1980s. The latter role suited him. Although he was just 5-foot-10 and never weighed more than 180 pounds, Lane loved the violent nature of the game, believing his best position would have been safety, not cornerback or running back.

“I just loved hitting,” he said. “Even though I was smaller than everyone, everybody that knew me would say, ‘Shaun will light you up.’ That became a part of me.”

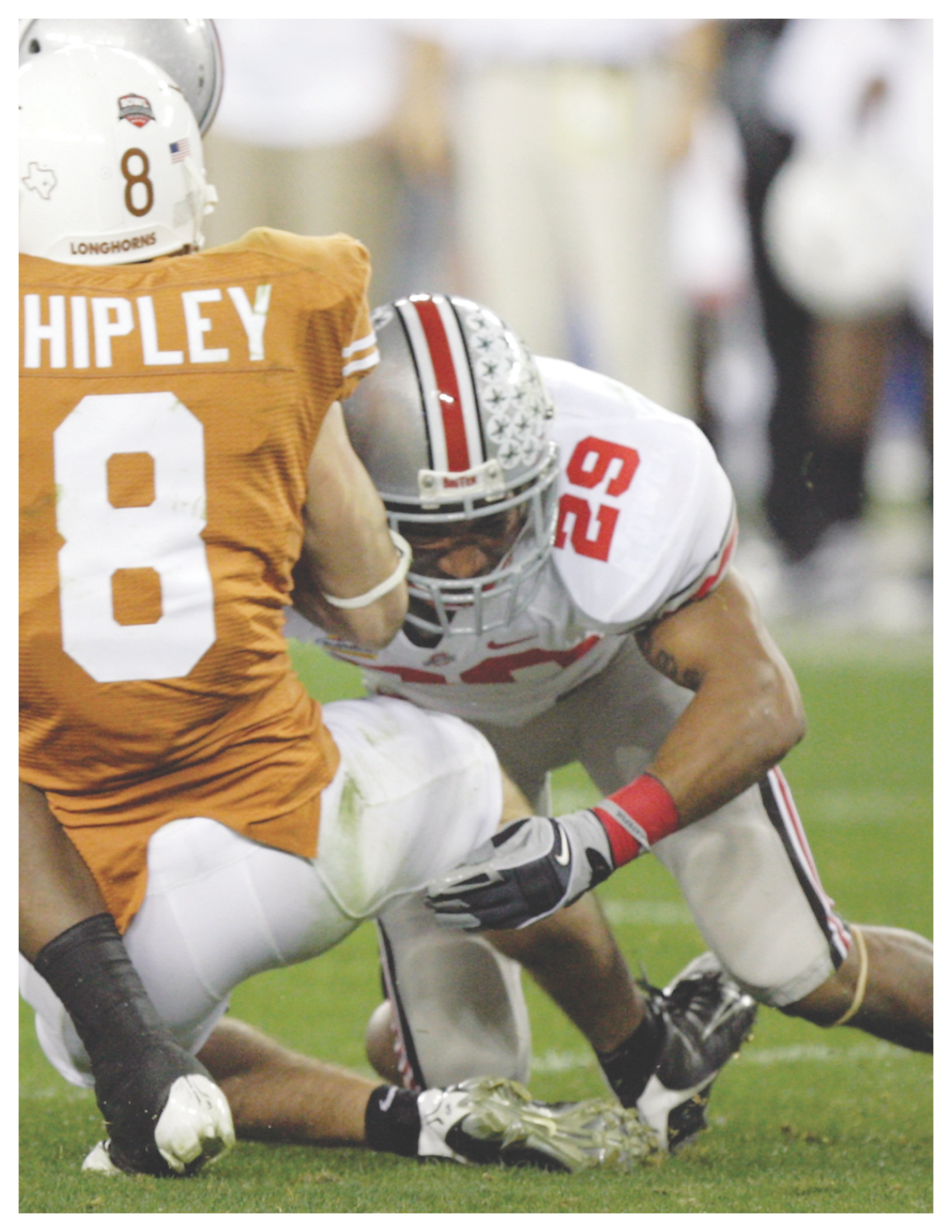

Ultimately, too big a part. With 5:39 left in the second quarter and Ohio State leading 6-3, Texas junior Jordan Shipley fielded a kickoff at the 3, ran straight ahead for 20 yards, made a slight cut to the right and ... “everybody moved out of the way,” Lane said. “That’s how it felt in my head. Everybody moved and it was just me and him. I just ... boom. Ran full speed. Didn’t even try to break down. Just tried to run through him.”

With his head up and his knees slightly bent, Lane lowered his right shoulder into Shipley’s right side, hammering him to the turf. It was a textbook play — “A picture-perfect tackle,” as his high school coach, Jeff Bayuk, put it — and Lane immediately rolled onto his back as the right side of his body went numb. One of his teammates, Aaron Gant, picked him up off the ground to celebrate and Lane said, “‘Hey, man, where’s my arm at?’”

“I couldn’t feel it,” Lane said of his arm. “I thought it might have come off or something. But he’s like, ‘What? It’s there.’”

Up in the stands, Lane’s future wife and the mother of his 2-year-old daughter, Tierra (Cayson) Lane, was sitting next to his mother, Denella Stanford. Both were at their first bowl games. Not realizing her son was the one injured, Stanford turned away for a second as the stadium got quiet. Cayson turned to her and said, “That’s Shaun.”

Stanford said, “No, no,” but Tierra insisted, “That’s him.”

“My heart just dropped,” Stanford said. “I was just frozen for a minute. It seemed like it took forever for anything to happen and I just asked the Lord to help.”

Play stopped for 20 minutes as Lane was strapped to a stretcher and eventually carted off the field, pumping his left hand and giving a thumbs-up as he left. On the TV broadcast, analyst Tim Ryan said, “He did everything right. That’s just a hazard of the game. As he hit Jordan Shipley, his head’s up, he gets it to the side. Everything looked good until contact was made. So many times when you see a guy get injured and taken off like that, he’ll hit with his head down and get caught in an awkward position. All of that looked right for Shaun Lane.”

It went wrong anyway.

Dealing with the aftermath

Ohio State’s trainers originally diagnosed Lane with a bad stinger. His leg had started twitching while he was still on the field and he regained feeling before he was strapped to the stretcher, but his arm wouldn’t respond. The trainers decided to send him to a Phoenix-area hospital — “Mostly as a precaution, they told me” — where he had an MRI on his shoulder. He stayed in Arizona for a week afterward. His mother stayed with him the entire time.

Ultimately, he was diagnosed with an avulsion of the brachial plexus, meaning his nerves were essentially ripped from his spinal cord and had no chance to recover. Worse yet, he felt constant pain in his arm, similar to the painful feeling you get when it falls asleep. His only hope for recovery was through nerve transfers, where surgeons take nerves from less-important muscles and transplant them into the damaged shoulder, hoping they’ll take. He had two surgeries, both at Washington University in St. Louis, both more than 12 hours long. The first was in November of 2010, the second in February of 2012.

As the doctors worked on his physical recovery, Stanford worked on the mental part. She took a cell phone picture of him while he was still asleep after the first surgery and put it inside a picture frame engraved with Jeremiah 29:11: “‘For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord. ‘Plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.’” It’s now in Lane’s house in Columbus.

“When you see your child come in there [the hospital room] wrapped up like when I first saw him after giving birth, wrapped from head-to-toe to keep warm, I did not want him to get discouraged,” she said. “I just looked at him and saw all his dreams and all the things he wanted to accomplish and I did not want that to be the main thing in his mind. I wanted him to know there was more to Shaun Lane than just football, that God has a plan.

“I knew he had heard it a million times, but I knew this was one of the times when he was gonna have to hold onto it.”

As he waited for his arm to recover — doctors told him it could be weeks or years — Lane immediately dropped weight, to the point where his teammates struggled to recognize him. At his peak, he could bench-press 370 pounds but he had to re-learn how to write (he’s right-handed), tie his shoes (he uses his right foot as a stabilizer), put on clothes and change diapers.

“You just learn to think outside the box,” Lane said. “You’ve got to think of different ways to get it done. But that translates to the rest of life. The solution isn’t always obvious.”

As the months wore on, his arm failed to respond and reality set in. So did depression. Between January and the fall, Lane figures he went outside four or five times. He wasn’t comfortable socializing, knowing the first thing people did was hold out their right hand to shake it. He struggled with losing football, struggled with not being able to provide for his family. Ohio State handled his medical bills, but the way its insurance worked, for Lane to get anything more, he would have had to lose use of both arms, or an arm and a leg.

During that dark period, he mostly stayed in the house with his daughter, Gianna, watching cartoons like “Yo Gabba Gabba!”, “Bubble Guppies” and “Baby Einstein.” His family did what they could — Denella wrote a lot of encouraging notes, filled with Bible verses and Tierra never wavered from his side — but it wasn’t until November, when Lane got a job at Nationwide, that he started to move on.

“I know he gives the brighter side of it and he’s in a great place now, but to watch everything he worked for basically snatched from him, it was really hard then,” said Tierra, a 2004 Warren Harding High graduate. “There’s nothing more irritating than to hear about someone who’s gone through something as tough as he has and be like, ‘God got me through it.’ Well what about the days when you hated life or you didn’t want to get out of bed because you lost use of your arm? You weren’t born like this. He did experience that. It’s part of the journey.”

Football past and future

Thing is, his mom never wanted Lane to be a football player. His dad, South High graduate Garcia Lane, was an all-conference defensive back for the Buckeyes who later played two years for the Kansas City Chiefs in the mid-1980s, but Shaun wasn’t close to Garcia growing up, and Denella didn’t want her three sons getting hurt. Besides, the family went to church on Friday nights (and Tuesday nights and Sunday nights and Sunday morning), so Lane only ran track until eighth grade, when he snuck onto the football team, getting home from practices before Denella got home from work. (Hours before the first game, his eighth-grade coach had to call Denella, begging her to let him play.) His natural gifts were obvious and, a year later, he was the starting cornerback at Wilson. Two years later, the starting quarterback.

He and his younger brother, Ben, transferred to Hubbard midway through his sophomore year. Ironically, his coach, Jeff Bayuk, had scouted Garcia Lane when he was a first-year assistant at Ursuline. When Irish coach Dick Angle asked if they could beat South, Bayuk told him, “Not if Garcia Lane is playing.”

Shaun quickly blossomed into one of the area’s best players, rushing for more than 3,700 yards over his final two seasons and earning a scholarship with the Buckeyes, whose coach, Jim Tressel, had coached Garcia at OSU.

“I’ve been coaching since 1978 and I would say, if he’s not my favorite player to coach, he’s certainly in the top five,” Bayuk said. “I’ve coached a lot of really good kids and he’s very special, not only as a player but as a person. He’s a special person.”

Lane redshirted his first season at Ohio State in 2004, then tore his ACL as a freshman playing special teams. After a brief stint at tailback in 2006, he moved back to corner and finally started seeing the field as a junior. But with the Buckeyes loaded at defensive back — one of their corners, Malcolm Jenkins, won the Jim Thorpe award in 2008 — he briefly considered transferring to play his senior year at Youngstown State with his brother Ben. Ultimately, he stayed in Columbus and was voted OSU’s Special Teams Player of the Year.

“Shaun is one of the great kids in the world,” Tressel said. “He was a great kid to have on the team. Always smiled. Always worked hard. Good student. Just a team guy. I can’t think of even one little problem we had while he was there. He did everything right.

“That’s why I shake my head when I think about what happened. In my first year of coaching, when I was at Akron in 1975, we had a kid die in a game. In my 37 years, this was probably the next-worst injury [in a game].”

Lane’s arm still hurts, but he’s learned to live with the pain. He can’t move anything below his elbow, but he can move the upper part of his arm. It would be easy for him to blame football, or to wish he had never played, but he can’t do it. Football gave him an education, an outlet for his competitiveness, a chance to use his gifts.

“I can’t say I regret it, and I wouldn’t discourage anyone from playing, either,” he said. “You have dreams in life and you have to follow those dreams. I had dreams to play football and make it big. If you don’t have dreams to chase, what do you really have? I enjoyed chasing it as long as it lasted.”

His mom, though, still struggles to watch the sport. She hasn’t been to a game since Ben’s YSU career ended.

“Any time someone goes down and doesn’t get up, it just grips me,” she said. “I just start praying, whoever it is.”

Looking ahead

Lane and Tierra got married in 2011. They have two kids: Gianna, 8, and Leilani, 3. They live in a nice middle-class neighborhood in Hilliard, a Columbus suburb. Lane works as an operations manager at Wal-Mart. Tierra is (technically) a stay-at-home mom, but she works a few times a month, either at her friend’s accounting firm, as an orthodontist assistant or as a substitute teacher. By all accounts, it’s a good life.

“I’m a manager and people tell me their problems, so I hear them out,” Lane said, grinning. “Then I tell them, ‘You don’t really have a problem. You think you do, but it could be so much worse.’ And that’s the same thing I live off of. It could be so much worse. My leg could have not come back. I have teammates, like Tyson Gentry, who got paralyzed at practice. I know my situation could be 20-30 times worse.

“Everything happens for a reason. My purpose is to help other people out.”

Outside of the lost muscle, Lane still looks like he did in college. He misses competing — “That’s the hardest thing, because you can’t mimic it,” he said — but he enjoys watching Gianna play soccer, where “she’s quicker and faster than everyone by far,” he said, smiling. She gets that from both sides: Tierra’s brother, Josh, was a standout running back at both Warren JFK and YSU.

“People are like, ‘How did she get so good?’” Lane said. “I just smile. I don’t even tell them I played football.”

At this point, Lane knows it would take a miracle for his arm to recover. (“Which I do believe in,” he said.) But he’s long past dwelling on it. He can still do most things and Tierra handles things he can’t (like cutting the grass).

“I try to go along with life and take it day by day,” he said. “I don’t get too caught up in the thought of it.”

Said Bayuk: “When he was inducted into our Hall of Fame [a few months ago], I think it [the injury] was the first time he ever even acknowledged it. I don’t know how I would handle something like that, but he seems undaunted by it.”

Among athletes, maybe the most overused — and misunderstood — verse in the Bible in Philippians 4:13: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.” But it’s clear, through the previous two verses, that Paul is talking about an attitude, not an accomplishment. “I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances. I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want. I can do all this through him who gives me strength.”

It’s been more than six years since his injury, but Lane learned the secret of being content a long time ago. That spirit of thankfulness he had before the bowl game? He still has it.

“Especially when I think of how bad the situation could have been,” he said. “Not to say that I’m not frustrated just as often, but I can control those emotions when being thankful.

“When you ain’t got nothing else to hold onto, there’s still that sense of hope. That’s what I had and that’s what I have to get me through.”

43

43