RELATED: State: Too soon to say if Poland quakes will delay Weathersfield well

By Tom McParland

tmcparland@vindy.com

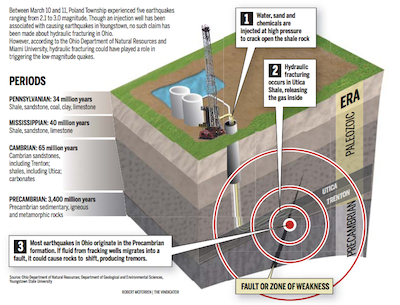

Source: Ohio Department of Natural Resources; Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Youngstown State University

YOUNGSTOWN

We’ve heard it since the dawn of the fracking boom in the Mahoning Valley: Fracking doesn’t cause earthquakes.

Beginning in 2011, a swarm of as many as 109 quakes hit the Valley. Eventually, the cause was linked to an injection well at D&L Energy Inc. on Salt Springs Road, which had penetrated the Precambrian crust with fracking waste.

That acknowledgement was slow to come. In October 2011, Heidi Hetzel-Evans, a spokeswoman with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, told The Vindicator “[ODNR has] not seen any evidence that shows a correlation between localized seismic activity and deep-injection well disposal.”

By the following March, the ODNR was on board, telling the Valley what it had suspected for months: an injection well triggered quakes.

Two years later and 12.5 miles away, a 3.0-magnitude earthquake shook Poland Township just before 2:30 a.m. In total, geologists have recorded 12 low-magnitude quakes, all near the Carbon Limestone Landfill.

This time, there was no injection well at the site — only fracking wells.

This month’s events have led the Valley to wonder, again, whether the fracking process can trigger earthquakes, given the right geological conditions.

Geologists are examining a hypothesis that would link the Poland tremors directly to fracking at the landfill.

The theory — that fluid from a fracking well could have seeped into an unknown fault extending upward from the Precambrian basement — is being considered by outside observers, while ODNR spokesmen remain tight-lipped.

Thomas Serenko, chief of ODNR’s geological survey division, laid out the scenario last week while responding to a Vindicator interview via email.

The state’s top geologist said “all preliminary indications” show the quakes occurred in the Paleozoic rock sequences and not the Precambrian basement, where the Youngstown injection-well quakes occurred.

“[Seismic events] are far more likely to occur in the Precambrian than in the overlying Paleozoic,” he said.

The location is unusual because most of Ohio’s earthquakes happen in the Precambrian formation, along ancient faults and zones of weakness that are antagonized by crustal stresses. Those faults are older and more stressed than the Paleozoic faults that lie above.

Not only is the depth unusual, but it is also close to the depth of fracking wells that were drilled at the Carbon Limestone Landfill.

Hilcorp Energy Co. was in the process of completing six wells at one of its two pads at the site, when the March 10 quakes struck.

An ODNR spokesman confirmed that at least one of those wells was being fracked at the time.

ODNR ordered all activity at the pad shut down, while another well at a separate Hilcorp pad continued to produce.

Hilcorp said the wells under development were drilled to an average depth of 7,900 feet.

At that depth, the wells penetrated the Trenton Limestone, a rock layer just below the Utica Shale and located in the Paleozoic formations, Serenko said.

Serenko’s assessment caught the attention of Ray Beiersdorfer, a geology professor at Youngstown State University, who has floated a “working hypothesis” that the tremors were the product of fracking.

“If the earthquakes happened in the Paleozoic rocks close to the well [and] while the well was fracking this provides strong evidence that fracking was responsible as a trigger,” he wrote in an email.

Mike Brudzinski, a professor of seismology at Miami University in Oxford, said the quakes all occurred at a common depth and generally had an east-to-west orientation, suggesting that they all occurred along an unknown fault line.

Despite ODNR’s spotting of the earthquakes’ depth, Brudzinski said the early data are not conclusive as to whether the actual location was in the Paleozoic sequences or the underlying Precambrian basement.

He added that the regional seismic network in the area limited determining the time and space of tremors from a distance.

According to his analysis, the earthquakes could have originated within a vertical range of two-thirds of a mile to nearly 1.5 miles. The shallow end of that spectrum puts them near Hilcorp’s wells. The deepest end locates them in the shallow part of the Precambrian.

In the email correspondence, Serenko noted that many of the Paleozoic faults actually originate in the Precambrian and propagate upward.

If the earthquakes actually did occur in the basement formation, Beiersdorfer said it is possible that fluid could have escaped the fracking horizon and seeped into one of those faults, causing rocks to shift and produce tremors below.

Brudzinski agreed with the premise. Should it be determined the earthquakes occurred in the deeper rock, he said, it would be a leading theory to explain the quakes.

While the connection between injection wells and earthquakes has been well-documented in the past few years, a link between the fracking process and seismic events remains unclear.

Geologists point to only three instances where fracking was the cause of earthquakes. In Oklahoma, British Columbia and Great Britain, fracking has been linked to a series of low-magnitude tremors, registering from 2.0 to 3.0 on the Richter scale, according to United States Geological Survey.

But the instances are exceedingly rare, given the number of hydraulically fracked wells in this country — 1.1 million, according to FracTracker — and abroad, raising the point that site-specific geology plays a key role in determining if quakes occur.

“There seems to be something about the geology [in Mahoning County] that’s really throwing up a red flag that we shouldn’t be doing either of these activities in this vicinity,” Beiersdorfer said at a press conference earlier this month.

The underlying rock formations and the faults they may hide remain somewhat of a mystery here.

Much of what is known about the Precambrian is held by geophysical companies as proprietary information and sold to oil and gas companies looking for resources in the overlying Paleozoic sequences, Serenko said.

“There is no public seismic reflection information available for Mahoning County,” he wrote.

“Our knowledge will be enhanced if additional Precambrian penetrations are drilled in this region,” Serenko added.

There is much to be learned about these earthquakes.

Though ODNR established a network of 13 seismic monitors in the region after the 2011 quakes, the agency has not yet moved any to the Hilcorp site.

USGS and Lamont-Doherty have both expressed interest in setting up their own monitors, but neither has taken action, likely out of professional courtesy to ODNR.

Beiersdorfer has joined in the chorus of geologists and activists urging ODNR to place seismic devices at the Poland site.

“These should be deployed before they start fracking again, and they should keep them there while that’s happening,” he said.

As of last week, Hilcorp’s fracking wells remained shuttered.

ODNR said the company is cooperating and actively turning over logs to the agency.

The agency said it is still too early to determine the cause of the quakes, but it continues its review of the events.

43

43