Fight of a lifetime

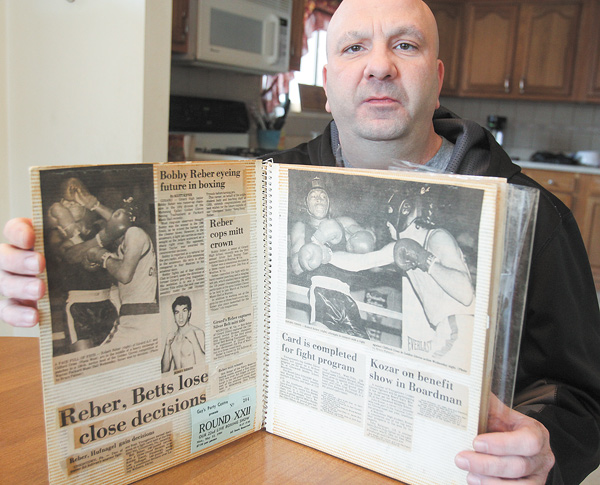

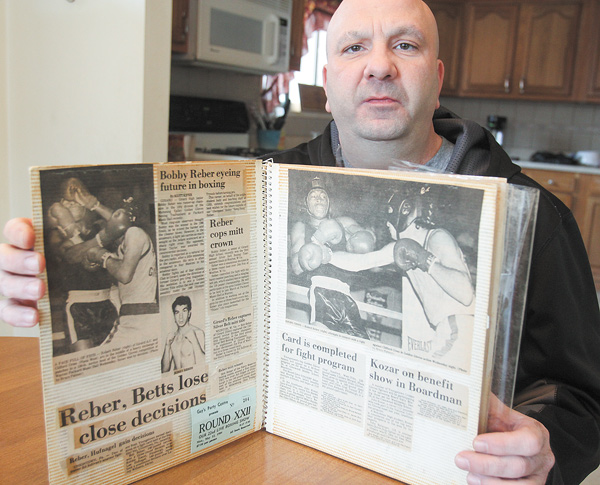

Reber holds a scrapbook of clippings from his boxing days. He now suffers from dementia, which he says is a result of injuries suffered while boxing.

CONCUSSIONS: PAYING THE PRICE

Golden Gloves winner Bobby "Bang Bang" Reber fights dementia, Parkinson's

By Kevin Connelly | kconnelly@vindy.com

YOUNGSTOWN

Before he was known as Bobby "Bang Bang" Reber in the ring, the former professional boxer was getting into fights at St. Anthony's School in Brier Hill.

Robert Reber recalled the first time he ever stepped into the ring at age 1 2.

It was love at first fight.

"It was the only way I could fight and not get suspended," Reber said with a chuckle.

Now 45, Reber lives on the South Side with his two kids, Sidney, 12, and Paul, 9; and his fiancee, Stephanie King.

And he still feels the impact of his previous lifestyle.

He suffers from dementia and is showing early stages of Parkinson's disease, said his doctor, Sandy Naples.

Reber was a Golden Gloves winner in 1986, 1987, 1989 and 1990.

His first big break came on March 16, 2002, when he fought in the super-middleweight card at W.D. Packard Music Hall in Warren. He defeated Casey Leathers by unanimous decision.

Reber's professional boxing career took off, though four years later, he had to have surgery on his left eye to replace a detached retina.

That was the first of nearly a dozen operations he would be forced to undergo due to injuries suffered in his boxing career.

Despite a number of doctors and family members advising against it, Reber would extend his career and, ultimately, extend the punishment to his body.

"I had to put clothes on my kids' backs and food on the table," Reber said. "I did it for the money and really needed it."

The worst news came in 2008 when he was diagnosed with dementia and was told he was showing early stages of Parkinson's disease.

Reber didn't want to believe it. He went for a second opinion, where a neurologist at Cleveland State University confirmed the diagnosis.

Even after the life-altering news, when money talked, Reber fought.

"Things just started falling apart," he said. "All those years of my shoulder popping out, and I would just get shot up to numb the pain.

"I mean that's just what everyone did, and I knew what I was doing to my body, but I needed to fight."

Later that year, he took what would be his last fight in West Virginia. Reber still remembers the phone conversation.

"They said if I could make it 10 rounds then they'd give me $10,000," he recalled. "Of course I said I'd do it. That was good money."

At that point Reber was a 40-year-old man with an 80-year-old's body. The abuse he took in the ring was just the opening round of a life-long fight against time.

He earned his $10,000.

"Punchy with a bad memory"

Reber's condition was worsening. His balance was off. His speech was beginning to slur.

"[The public] doesn't see the after life of how it affects you," Reber said. "I have two little kids that I'm raising, and they're helping me with housework because I can't do it."

Dr. Naples is a primary-care physician in Poland, and the Chaney grad grew up around boxing.

Dr. Naples began seeing Reber 21/2 years ago and described the former fighter as "punchy" with a bad memory. He said he wished he had a baseline test on Reber, but can tell from observing other boxers he's taken care of over his 23 years of practice that Reber has all the same signs of dementia.

"A lot of it depends on how they take care of themselves," Dr. Naples said. "If they continue to work out and live a healthy lifestyle that's great, but a lot of them don't and I think they're more susceptible."

When Dr. Naples learned of Reber's decision to continue fighting even after the initial diagnosis of dementia, he could only assume further head trauma magnified and escalated the symptoms he's experiencing now.

"The recommendation [to continue to box] would be absolutely, positively no," Dr. Naples said. "They can clear a physical and get by, and cognitively they can be sharp enough to say, "Yeah, I can get in the ring."

"But is it the right thing? I think it's pretty apparent no, it's not."

"I Thought I was superman"

When Reber first sat down at the kitchen table at his home with a reporter in January, he began to look back through old photos of himself in the ring.

A big smile creased his face as he excitedly talked about past fights.

Reber guessed that he suffered more than 50 concussions throughout his career. He said he knew the risks involved when he got into the sport.

"There's just no way to make boxing safe," Reber said. "People pay for the blood and the knockouts. It's just the way it is, and the only way to prevent anything from happening would be to ban it."

Last month, his other son Derek, 17, moved in with his family. When Reber gets sick he tends to stay in bed longer, and Derek felt it was best if he came to live with them to help with the kids and around the house.

His youngest son, Paul, is a typical 9-year-old who is full of energy. Reber said he wouldn't think of letting his son pursue a boxing career.

In fact, he said he's even skeptical about allowing him to play football.

Then the old "Bang Bang" Reber surfaced as he thought back to all the people he ignored as a kid.

"I remember my pops and brother telling me I was gonna pay for it later, but I was young and, you know, thought I was Superman," Reber said. "I was invincible then, and now I walk with a cane."

Depression is also an issue for Reber. He said he thinks all the time to himself, "Am I gonna make it to see my son turn 18?"

A few weeks ago, Reber spent three days in the hospital for severe headaches.

"I wake up in the morning and have to sit down for an hour until my brain wakes up," Reber said. "I mean I've even forgotten my kids' names before so it's just umm, umm ..."

He paused mid-sentence.

"Sorry," he mumbled. "I just lost my train of thought. What were we talking about again?"

43

43