Wells on hiatus in Pennsylvania

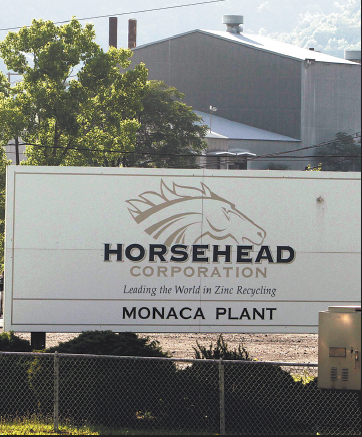

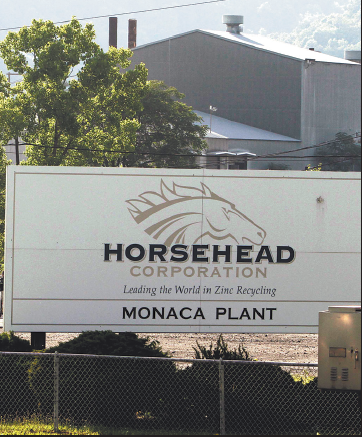

The sign at an entrance for the Horsehead Inc. zinc plant is seen in Monaca, Pa. Shell Oil Co. said in March that it had chosen this site near Pittsburgh for a major new petrochemical refinery that could provide a huge economic boost to the region. Shell Oil Co. is years away from building the petrochemical plant, but the company already is reaching out to the local community and getting a wholehearted welcome.

By Erich Schwartzel

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

PITTSBURGH

The gravel field near Mark Gera’s home in Derry has the trappings of a successful gas well: more than 200 yards of space cleared of trees and brush, a man-made pond guarded by an electric fence, and even a hole burrowed thousands of feet into the ground.

It’s only missing one thing: the well.

Natural-gas prices have fallen to the lowest levels in a decade, leading drillers to move rigs to places such as Ohio where more profitable natural-gas liquids and oil are available. As a result, the rigs have taken a hiatus in Derry.

The evidence can be seen on Gera’s property, where the hole has been drilled but the rock hasn’t been hydraulically fractured. No gas is coming to the surface to be fed into a pipeline — and no royalties will be paid until then.

In place of the normal action surrounding a drilling site, there’s an abandoned subcontractor truck and trailer, jersey barriers surrounding the drill hole and a sun-faded Sheetz coffee cup sitting atop a pump. A safety cone and mayonnaise packet also were left behind.

Officials at WPX Energy, the only driller in Derry, say they plan to return and resume drilling within two years, based on the expectation that natural-gas prices will rebound after a record slump.

“We consider it more of a pause,” said Susan Oliver, WPX spokeswoman.

It’s a muted letdown for a community that saw drilling start only two years ago with rapid-fire leasing that turned poor farmers into retired millionaires.

Derry’s experience offers a glimpse into a boom-bust cycle that is happening sooner than many expected, and at a much more fluid, month-to-month pace.

The bust hasn’t come in the form of dramatic bankruptcies or foreclosures. It’s more incremental than that — a reduced royalty check in the mailbox, an empty road that once brimmed with truck traffic, a delayed water project that can’t guarantee funding anymore.

Officials here have a new daily routine: scanning the newspaper to see if natural gas is trading high enough to bring the rigs back.

Money flowed like water

Derry’s first well was drilled in 2010, and the town of about 15,000 people quickly became the most-drilled part of Westmoreland County. Its expanses of farmland and community members familiar with conventional shallow drilling made it a friendly boom town.

The driller at the time was Williams, which in January spun off its drilling division, WPX Energy. WPX flew in workers from Texas and Oklahoma to work the Derry rigs, having the workers sleep on-site or stay in the Hampton Inn in Blairsville.

The community hustled to prepare for the industry, said Mark Piantine, fire chief at the Derry Volunteer Fire Department.

Company executives flew in from Tulsa in May 2010 to meet with him and other local officials on a drilling rig. Carpet was laid out for the occasion, which also featured a wet bar and portable toilets rented from a Latrobe company.

“They even gave me my own hat,” said Piantine.

Soon after the drilling began, Piantine met with 10 local fire companies and WPX executives to figure out how to help firetruck drivers find well sites that sit off unmarked rural roads.

Every well site now has a street number — and a mailbox. WPX seemed to have moved in.

WPX has 19 pad locations in Derry, with 43 wells drilled in the area. The company said 34 of those wells are producing gas. Many of the leases were signed for five-year terms at a going rate of about $2,500 per acre. Gas could flow for up to 50 years, the company said.

Farmers sold their cows, and the local water authority found a deep-pocketed customer that needed millions of gallons of water at a time.

The company spent $526,000 on a system that pumps water from nearby Latrobe to Derry to provide the water used to drill and frack a well. The system sits behind the township supervisors’ building, and when Supervisor Vince DeCario looks at it, he thinks the investment can’t be short term.

“Why would you spend half a million dollars and then leave?” he said. “They’re coming back. Definitely coming back.”

Williams quickly became the water authority’s biggest client — easily trumping Derry Area School District and the sewage plant — and paid the authority hundreds of thousands of dollars each year. The driller’s money helped counterbalance income lost when several dairy farmers signed leases and decided to sell their thirsty cows, said Rich Thomas, Derry manager at the water authority.

“They balanced our budget for a couple of years, and now they’re gone, and we’re being very frugal,” said Thomas.

Until WPX drilling and its money come back, the authority is postponing three projects: the consolidation of two pump stations, a waterline extension and an entirely new waterline in the nearby village of Peanut.

Driven by the market

Changes in the commodities market may be partially blamed for those postponements.

Over the past several years, hydraulic fracturing technology has unlocked inaccessible pockets of natural gas across the country.

The higher reserves lead to lower gas prices — much lower. Earlier this year, gas fell below $2 per thousand cubic feet for the first time since 2002.

The price has risen, hitting a six-month high this week as it edged toward $3. Oliver said WPX doesn’t have a “magic number” that would warrant bringing the rigs back to Derry, but industry analysts have said gas prices closer to $4 would shift priorities. The falling prices put a focus on “wet” gas, which comes out of the ground loaded with higher-priced liquids such as ethane and butane that can be stripped and sold.

WPX and many other companies have responded to the low prices in similar ways, moving rigs from “dry” portions of the state in the northeast to “wet” sections in southwestern Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Some cut back drilling projections altogether.

WPX Energy’s balance sheet reflects the financial incentive in drilling for liquids and oils. In the first quarter of 2012, the company’s oil and liquids production rose 26 percent from the same quarter one year ago, but its revenue from those resources rose 45 percent.

Before hauling the rigs away, WPX drilled but didn’t frack some wells, which activated leases to avoid having to renegotiate payment terms with landowners.

“We want to maintain our fiscal discipline,” said Oliver. The company also drills for natural-gas liquids and oils in shale formations in North Dakota and Colorado, among other states.

In Derry, about 10 workers tend to completed wells and compressor stations across WPX’s 25,000 acres of leased land. The company’s only active Marcellus Shale presence is in Susquehanna County, where leases were set to expire soon.

Compared with some towns home to the controversial industry, Derry’s approach is low-key and accommodating. Officials and residents had few complaints about the drilling. They just want to know, after all their preparation and expectation, when it’s going to start again.

For Gera, whose property has been cleared and readied but awaits a rig, the focus already has moved beyond the coming years to future generations. “Somebody from my family will benefit from it,” he said. “Even if it’s not me.”

43

43