Valley vet makes searching for MIA comrades his mission

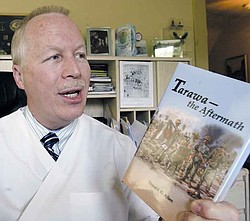

William D Lewis The Vindicator Dr. Don Allen, Boardman veternarian, shows a copy of a book he wrote during a 7-2-11 interview.

Paul Dostie, left, a retired investigator with the Mammoth Lake, Calif., Police Department, Buster, the cadaver dog he trained, and Dr. Donald K. Allen of Youngstown, are shown on their way to Tarawa, an atoll in the Pacific Ocean, to look for the remains of Americans declared missing in action in the battle with the Japanese in November 1943.

Dr. Donald K. Allen of Youngstown, a veterinarian and a military veteran, shows off 30-caliber bullets recovered from the Battle of the Bulge battlefield in Belgium. He has written a book to let people know what happened to their loved ones listed as missing in action.

Valley vet makes searching for MIA comrades his mission

YOUNGSTOWN

Finding Americans missing in action from World War II’s Battle of Tarawa and Battle of the Bulge is the passion of a local veterinarian and military veteran.

“It’s my mission to do what the government doesn’t have the time or resources or the will to do,” said Dr. Donald K. Allen of Youngstown, an Air Force veteran who served on active duty from 1967 to 1971 and retired as a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve in 2010.

The Battle of Tarawa in the Pacific Theater and the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium in the European Theater were two of America’s fiercest and most deadly battles, leaving many hundreds of Americans buried in unmarked graves and listed as missing in action.

During the Battle of Tarawa, an atoll in the Pacific, fought from Nov. 20-23, 1943, the 2nd Marine Division suffered 3,166 casualties including 894 killed in action and another 84 died later of their wounds.

The Battle of the Bulge was fought from Dec. 16, 1944, to Jan. 25, 1945, in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium, France and Luxembourg. The “bulge” refers to the bend in the Allies’ line made by an unexpected German offensive.

United States military forces, primarily the Army, suffered 89,500 casualties, including 19,000 killed, 47,500 wounded, and 23,000 MIA or captured who later died in prison camps and whose remains have not been found.

It is the remains of these men that Dr. Allen wants to see brought home.

His fascination with WWII began as a junior high school student. Then in the 1990s, he read “Tarawa — The Story of a Battle” by Robert Sherrod, a war correspondent for Time, who waded ashore at Tarawa with Marines on D-Day.

“The book was so vivid, I wanted to find out what happened after the battle. It was current history. I could reach out and touch those people,” he said.

He began extensive research on the battle, including visits to Tarawa in 1997 and 1999, to do research for a book. The excursions led to Allen writing and self-publishing in 2001 “Tarawa — the Aftermath.”

Allen has created an online addendum to his book that includes information from interviews with some 100 Tarawa veterans, mostly Marines and Navy corpsmen and Seabees, and personal submissions by Marine and Navy personnel who fought on Tarawa, and their family members. The addendum can be accessed at www.tarawatheaftermath.com.

Teams from History Flight, made up of professional researchers, historians and ground-penetrating radar specialists, have found remains of 139 of the 541 Marines believed missing from the Battle of Tarawa.

But Allen’s latest excursion to Belgium and the Ardennes and the extensive use of a cadaver dog named Buster has him excited about finding a lot more MIAs from WWII and subsequent wars.

His primary function on the History Flight team was to take care of Buster, he said.

He said a client had told him about cadaver dogs and at about the same time, Mark Noah, founder of History Flight, contacted him about another trip to Tarawa. Likewise, he learned about Paul Dostie, a retired investigator with the Mammoth Lake, Calif., Police Department, who had trained Buster by taking him to “boot hill” cemeteries in western “ghost towns.”

Allen said the 7-year-old dog can detect chemicals created by decaying bones deep in the ground that make their way to the surface. Buster lays down on the site to signal to his handler that he has found something.

Allen said the cadaver dog was underutilized on a MIA-search trip to Tarawa in February 2011. “We needed to have our own objectives and maps and driver,” he said.

But in Belgium last June, the itinerary was better planned, mainly due to the cooperation and support of their Belgian teammates. The team with Buster knew who they were looking for and in general where to look, he said.

Allen said he is convinced Buster’s value will be proven when the sites are excavated by the Belgians and U.S. Department of Defense personnel this fall. The History Flight team does not excavate sites. It notifies local and U.S. DOD officials of the sites it believes will yield remains.

“I will not feel complete until the remains of specific individuals are found where Buster signaled they were. That would open the door to further search using cadaver dogs at other places where Americans were overrun in the war,” he said.

In the same vein, Allen has researched deck logs of transport and supply ships that traveled between Tarawa and Hawaii after the battle. The logs listed military personnel buried at sea (BAS). The Punchbowl Cemetery in Hawaii has many Tarawa casualties listed as both BAS and MIA. How could they be both, he reasoned.

By studying the logs, he was able to determine the longitude and latitude of 100 of those listed as BAS/MIA, allowing removal of the MIA designation. He then notified their families where their loved one was buried.

“I have received emails from families thanking me for that research,” he said.

Allen said that what Americans did in WWII remains fresh in the minds of Belgians. It was brought home to him when he visited the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial, which contains the graves of 7,992 members of the American military who died in World War II.

A Belgian couple approached him, and when they learned he was American, said how grateful they are for what America did for them in WWII.

Allen said that meeting further encouraged him to continue his efforts to find the remains of MIAs.

“We owe them that.”

43

43