Penn State looks to new week

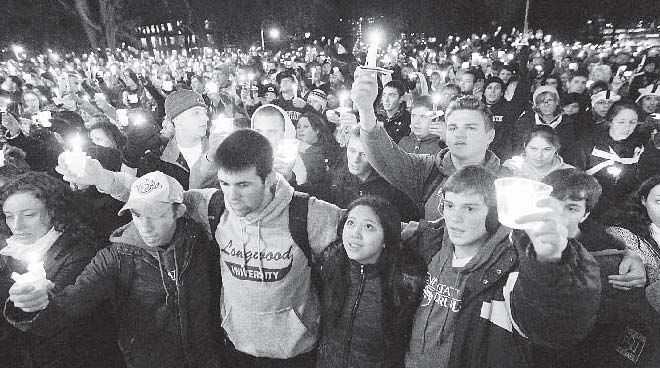

In this photo from Friday, people gather in front of the Old Main building for a candlelight vigil on the Penn State campus in State College, Pa., in support of the reported victims of a child-sex-abuse scandal involving a former assistant coach. As Penn State leaves a harrowing week behind and takes tentative steps toward a new normal, students and alumni wonder what exactly that means.

Associated Press

STATE COLLEGE, Pa.

For Penn State University, there was the past week — a week of unimaginable turmoil and sorrow, anger and disbelief and shame. And then there is tomorrow.

As Penn State leaves a harrowing week behind and takes tentative steps toward a new normal, students and alumni alike wonder what exactly that means. What comes next for a proud institution brought low by allegations that powerful men knew they had a predator in their midst and failed to take action? What should members of its community do now?

“Our best,” said Julie Weiss, 19, a sophomore from Wayne, N.J., pausing outside her dorm to consider the question.

Last week, the worst in its 156-year history, the place called Happy Valley became noticeably less so. Students and alumni felt betrayed as child-sex-abuse allegations exploded onto the nation’s front pages, bringing notoriety to a place largely untouched by, and unaccustomed to, scandal.

As the school’s trustees pledge to get to the bottom of the saga, many Penn Staters are feeling sadness, anger, a sense of loss. Some can’t sleep. Others walk around with knots in their stomachs or can’t stop thinking about the victims. Wherever two or more people congregate, the subject inevitably comes up.

“Everyone’s been struggling to reconcile how something so bad could happen in a place that we all think is so good,” said senior Gina Mattei, 21, of Glen Mills, Pa., hours after Penn State played its first game since 1965 without Joe Paterno on the sidelines as head coach. “It’s sad to think that something like that could happen HERE, in a place where everyone is really comfortable and has a lot of community spirit.”

Penn State’s former assistant football coach, Jerry Sandusky, was charged Nov. 5 with molesting eight boys over a span of 15 years, and two university officials were charged with failing to notify authorities after being told about a 2002 incident in which Sandusky reportedly sodomized a boy in the showers of the football building.

The scandal quickly metastasized, costing two more key figures their jobs — Paterno, the face of Penn State football since 1966, as well as university president Graham Spanier. It also tarnished the reputation of an institution that preached “success with honor” — that, according to its own credo, was supposed to be better than this.

Some students argue that the question itself — “How does Penn State regain what it’s lost?” — is flawed. This remains a world-renowned research institution, they point out. It’s still the place where students hold THON, a yearly dance marathon that raises millions of dollars for pediatric cancer research. It’s far more than football and far bigger than Sandusky, Spanier, even Paterno.

“I don’t think that our name is tarnished at all,” said Amy Fietlson, 19, a sophomore and aspiring veterinarian from New Jersey. “The integrity of a few individuals who have been involved with this school is definitely tarnished, but for the rest of us that had no way of preventing it or had no involvement in it, we are not tarnished at all. Our integrity remains.”

The U.S. Education Department is investigating whether the university violated federal law by failing to report the reported sexual assaults. Some donors are expected to pull back, at least in the short term. One football recruit has already changed his mind about attending Penn State next year. Moody’s Investors Service Inc. warned that it might downgrade Penn State’s bond rating as it gauges the impact of possible lawsuits.

Then there’s the risk that new allegations of wrongdoing — more abuse victims coming forward, perhaps, or evidence of a wider cover-up than what’s already been alleged — could jolt the campus again.

“I hope and I pray that it doesn’t go any further than what we’ve already seen, which is as tragic as it gets,” said George Werner, 47, a Penn State graduate who was tailgating with friends Saturday in the shadow of Beaver Stadium.

Werner, 47, who lives outside Ann Arbor, Mich., said he fears it will be a long, long time before the university gets back to normal. “Maybe not in my lifetime,” he said.

43

43