How safe are our natural-gas lines?

A fire rages after a natural gas explosion in Columbiana County on Feb. 10. No one was injured.

By Karl Henkel

YOUNGSTOWN

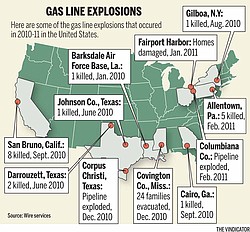

About two weeks ago, residents of Allentown, Pa., became the latest victims of natural-gas leaks and explosions, when five died after an unexpected blast.

It was another highly documented blast, similar to one in San Bruno, Calif., which killed eight in September.

Closer to home in Columbiana County on Feb. 10, a 36-inch pipe exploded in an open field. The explosion reportedly shook nearby homes but injured no one.

And that incident is on the heels of explosions in Fairport Harbor on Jan. 24 that destroyed 10 buildings and caused evacuation of more than 1,500 residents.

So how safe are Ohio’s natural-gas pipelines, and could a deadly explosion happen in the Buckeye State?

Though various aspects — faulty computer systems and incorrect pipe sealing — have been blamed in other accidents, Ohio is trying to take steps to prevent natural-gas accidents and improve safety.

Each state is required to follow federal mandates from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. In Ohio the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, a state regulator of utility services, oversees natural-gas providers such as Columbia Gas of Ohio, Everflow Eastern, Inc. and Dominion East Ohio, according to Matt Butler, spokesman for the PUCO.

Butler said the PUCO enforces all federally mandated natural-gas laws and said Ohio has nine investigators auditing every natural-gas line in the system at least once every two years.

He said the audits include spot and office-record checks and when PUCO detects a violation, it can assess fines and other penalties to help “minimize similar errors in the future.”

PUCO can issue fines up to $100,000 per day for intrastate violations, Butler said. It’s up to the federal government to assess fines on interstate pipelines, normally large distribution pipes.

In 2010, PUCO issued 29 “letters of probable non-compliance” to pipeline operators, which included 122 violations. In all 29 instances, the operator “remedied the violation[s] or submitted a plan for how they will address the violations,” Butler said.

One of those last year dealt with Dominion East Ohio — operators of the nation’s largest natural-gas storage system. Dominion could not document completion of some of its leak surveys in a “timely manner.”

Butler said Dominion “agreed to perform a manual review of all 52,800 leak-survey areas, comparing leak -survey data from old leak- survey systems, their centralized compliance tracking database, and their GIS database” and “agreed to submit quarterly status reports to PUCO ... beginning April 1, 2010.”

Dominion also agreed to a $300,000 civil forfeiture if it didn’t fulfill its obligations by Aug. 31. It followed through, and no fine was assessed.

John Williams, PUCO’s director of service monitoring and enforcement, said Dominion couldn’t properly document whether it had done the leak tests, so it was required to recheck them.

In the Jan. 24 explosion in Fairport Harbor, Dominion, in its preliminary report, could not determine why its pipes became overpressurized. A follow-up report is due in late March.

Dave Rau, communications and community-relations manager at Columbia Gas Ohio, said his company had one reportable incident last year, when its Toledo facility caught fire in November. Though the final report is not yet completed, a third-party preliminary report said the “fire was caused by a power line that fell onto the facility,” said Rau, who added the power line fell during a storm.

Columbia Gas Ohio serves 61 of 88 Ohio counties — including Mahoning, Trumbull and Columbiana — and spans more than 25,000 square miles. Its customer base tops 1.4 million and is the largest natural-gas utility in the state.

In 2008, it began a 25-year, $2 billion project to replace aging pipes as preventive maintenance.

Steel and cast-iron distribution pipes will be repaced with with much sturdier plastic that Rau hopes will “last for generations.”

“It reaches a point where it becomes more expensive to fix a leak than it is to replace it [pipe],” he said.

Rau said transmission lines are inspected every seven years using one of three techniques: inline inspection, or “smart pigging,” where a computer collects and records information about a pipeline, pressure testing and direct assessment, where instruments above ground excavate some of the pipeline for testing. In addition, leak surveys are done twice a year.

Distribution lines are tested more regularly. Pipes in business districts are tested every year, according to Columbia, every five years if the pipe is outside a business district and made of plastic or cathodically-protected steel, every three years if it has a mixture of plastic or steel or all steel and is outside a business district.

Rau said streets or areas are not neglected based on their population.

“If there’s a block or two that have just a few people, they’ll be lumped into a larger area,” he said.

The explosion in Columbiana County, which erupted on a farm, was a gas line operated by Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co.

Richard Wheatley, a spokesman for Tennessee Gas, said the pipe was tested according to regulations, including leak surveys. The last documented leak survey on the pipeline in Columbiana County was in May 2010, and the company did visual and aerial checks in November. Wheatley also said an aerial check had occurred “several days” before the Feb. 10 accident.

Tennessee Gas is investigating the explosion.

Carl Weimer, executive director of Pipeline Safety Trust, a nonprofit public charity promoting fuel-transportation safety, said despite the highly visible recent cases in San Bruno, Allentown and Columbiana County, pipeline explosions have decreased.

“I think there’s been kind of a heightened awareness,” Weimer said. “There was the big oil spill in Michigan, then there was the San Bruno explosion and now Allentown. Those stories are making the media more, so everybody’s more aware of pipelines and pipeline failures.”

According to the PHMSA website, there were 32 significant gas distribution incidents in Ohio from 2001 to 2010, resulting in 16 injuries, four deaths and more than $10 million in damage.

The annual U.S. average is 76 incidents, 43 injuries and 11 deaths.

“When you look at the actual statistics, with the raw number of failures happening across the country, it hasn’t really changed very much,” Weimer said. “It doesn’t look like there’s way more failures happening.”

43

43