Players must move beyond their football careers

Former linebacker Mark Brandenstein stands near the spot where he suff ered his third, and fi nal, concussion in the spring. An exercise science major, he now works as a student assistant for the strength and conditioning staff .

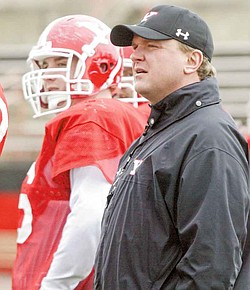

After getting cut by the Phoenix Cardinals in 1994, Eric Wolford, right, started his coaching career at his alma mater, Kansas State. Fifteen years later, he was hired as the head coach of Youngstown State.

By Joe Scalzo

YOUNGSTOWN

The kid who was born to be a line- backer — who started playing football in first grade and who plans to “die with a football in my hand” — stood at the 10-yard line at the north end zone of Stambaugh Stadium last week and pointed to the spot where his football career ended.

Mark Brandenstein remembers the play. Remembers bumping heads with an offensive lineman. Remembers blacking out and seeing spots and returning a fumble for a touchdown later that practice and “just not being right.”

“I knew it was bad but I didn’t want to face it,” he said. “I’m usually the kind of person where if I notice something like that, I at least tell somebody.

“But I didn’t say a word because I was so scared it might be it.”

It. The end. It was his third concussion in 18 months. You know how they say whatever doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger? That doesn’t apply to concussions.

“I kept practicing the whole day, figuring it would go away,” he said. “The next day I came in and it was worse.”

He told his coaches then sat out the rest of spring practice. He met with one doctor, then two more, hoping for a different answer. They all said the same thing: It’s only going to keep happening.

“The last doctor said, ‘You could redshirt [this season] but I don’t think it’s a good idea,’” said Brandenstein, who earned first team All-Ohio honors as a senior at Cardinal Mooney in 2009 and was a special teams standout last fall. “He said, ‘You’re becoming slower and slower as time goes on.’

“That really hit me.”

Soon after, the exercise science major joined the team’s strength and conditioning staff as a student assistant.

His sophomore year had just started. His post-football career had begun.

“Football is what I do. It’s me. When that time comes, it’ll be hard to walk away.”

Former Tampa Bay Buccaneers fullback Mike Alstott

“I want them to understand that this football thing is what we do. It’s not who you are.”

YSU defensive line coach Tom Sims

According to the NFL Players Association, about 100,000 high school students play football each year. Of those, 9,000 go on to play college football. Of those, 215 become NFL players.

Of those, about 43 will last more than 31/2 years in the league.

This is a story about life after football. The first player in this story saw his career end before his second season. The next one got a training camp invite. Two more played about a half-dozen seasons in the NFL. The fifth just ended his career and is still learning to live without the game.

All of them stopped playing before their 30th birthday.

All of them had to figure out what to do next.

“Sports is the only profession I know that, when you retire, you have to go to work.”

Former NBA player Earl Monroe

Eric Wolford’s professional football career ended a few weeks after it began.

After signing with the then-Phoenix Cardinals as an undrafted free agent guard in 1994, the Kansas State graduate spent most of his time in camp watching other players get reps in practice. He got cut after his first preseason game.

“The thing I found out real quick was, there’s a lot of guys out there hungry to play this game and the guys that play on Sunday, that’s a very elite level of people,” said Wolford, now the head coach at Youngstown State. “It was a great experience for me but very humbling.

“I realized at the end of the day that I was not at that caliber of athlete or talent.”

Wolford went back to Manhattan, Kan., where he got calls from Jacksonville and Denver.

“But I realized I was out of my league,” he said. “[Kansas State] Coach [Bill] Snyder knew I was back in town and said to me, ‘Wolf, I think you need to get into coaching.’”

Wolford decided to try it and worked that fall as a graduate assistant, running the offensive scout team against co-defensive coordinators Jim Leavitt and Bob Stoops.

“I took a liking to it,” he said.

Two years later, Leavitt was hired as the head coach of a new program at South Florida. One of his first hires was a promising young coach named Eric Wolford.

“Somebody will have to come out and take the uniform off me, and the guy who comes after it had better bring help.”

Hall of Fame Pitcher Early Wynn

If you’re a golfer or a clarinet player, you can play collegiately and keep playing for the next 60 years.

Football’s not like that. Fifty-year-olds don’t play football on the weekends like softball or soccer players. And playing flag football is sort of like eating sugar-free brownies.

YSU defensive line coach Tom Sims played seven years in the NFL: four with the Chiefs (1990-92, 1996), two with the Colts (93-94) and one training camp with the Vikings (1995). His career lasted 47 games.

When asked if his body told him it was time to quit, Sims started chuckling and said, “No, my coaches told me. Trust me. Several coaches. Several places.”

Sims was a classic overachiever. He played two years at Western Michigan, then transferred to Pitt his final two years. His career is the reason why he never tells a player they can’t cut it in the NFL.

“I’m living proof that it ain’t impossible, that an average, run-of-the-mill guy can achieve that level,” he said.

Sims graduated with a business degree but his only two goals in life were to be a football player and work with kids.

His first few years with the Chiefs he’d go to a community center after practice and coach a middle school flag football team. (“That was before I was married,” he said, laughing.)

After he got cut by the Chiefs in 1996, he contacted his former coach at Western Michigan, Jack Harbaugh, who by then had moved on to Western Kentucky.

By the summer of 1997, he was a coach. When asked what it was like not to be playing that first year, he said, “It was weird.”

“I still had the routine because of coaching so I was lucky in that sense because I’ve never been out of that routine,” he said. “But it was weird. It can be overwhelming to some people.

“I’m sure on some level, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t struggle with it. But the thing is, as long as you make it what you do, rather than who you are, you’ll be OK. Because it’s not a permanent identity. It’s a temporary identity. Who you are is much bigger than being a football player.”

“The end is always one play away. But you never think about that.”

Former NFL player Andre Coleman

Andre Coleman started playing football when he was 7. After a standout career at Hickory, where he led the Hornets to their only state title in 1989, Coleman played wide receiver at Kansas State, where he met a kid from Youngstown named Eric Wolford.

The speedy Coleman was a third-round pick in the 1994 draft by the San Diego Chargers and helped the team make it to the Super Bowl that season, where they lost to the San Francisco 49ers. Primarily a kick returner, he played two more years with the Seattle Seahawks and Pittsburgh Steelers before his career ended in 1998.

“I pulled a hamstring and for a guy like me, my speed was my strength,” he said. “When it’s over, it’s a tough pill to swallow.

“It’s pretty tough making the transitions from Saturdays, or in my case, Sundays, and seeing guys out there. You always get that bug to get back out there and play.”

Coleman kept getting calls from interested teams — “You’re still working out for teams, your name is still on the radar” — and admitted it took a couple years for him to accept the finality of it.

“Every year you’ve got guys graduating from college and you’ve got fresh legs coming in, so it’s always a new competition,” he said. “The longer you’re out of it, the tougher it is.”

Coleman used his college and NFL connections to become a successful businessman, working in real estate in Atlanta as well as a stint with New Era Sports Consultants, which represents pro football players.

Still, he missed the game. He talked to his wife, Brandi, about getting into coaching and they agreed if the right opportunity came up, he’d grab it. That opportunity came in the winter of 2010 when YSU’s new football coach was looking for someone to coach his tight ends.

“I don’t think I could have found a better situation,” said Coleman, now the receivers coach. “The coaching profession is a lot of hours, but it’s fun.”

“Football is not who we are. It’s what we do.”

Former YSU cornerback Brandian Ross, posting on his Twitter feed around midnight on Aug. 24

Over his four-year career at YSU, Bobby Coates played in 40 games and started 30, including 19 at right tackle. He earned second team all-conference honors last year as a senior and was named the team’s offensive lineman of the year.

He helped coach the linemen during spring practice, then sent his resume to every university he could find, hoping for a chance to coach. In the meantime, he got a job offer to Total Quality Logistics in Cincinnati.

“I said, ‘Hey, I’ll take it,’” he said. “It was between getting paid and not getting paid.”

On his first day of orientation, he stood up, introduced himself and mentioned he played football at Youngstown State. A few minutes later, another kid stood up, introduced himself and mentioned he played football at Missouri State.

“I played against him for five years,” Coates said. “It was funny.”

Coates wakes up every day around 5:45 a.m. to work out “just because I’m used to it” and admits he misses the game.

“I loved it,” he said. “I love football. I love the process, the workouts, the practicing, all that stuff. I learned as much if not more about life from football than I did from anything else.”

“Some guys are glad when it’s over and then they’re like, ‘Oh wait, now I’m in the real world and I have to wake up and go to work every day. They don’t realize how good they had it.”

Twenty four FCS players were drafted in April. None were from YSU. Two of Coates’ classmates, cornerback Brandian Ross (Green Bay Packers) and wide receiver Dominique Barnes (Detroit Lions) signed as free agents when the lockout ended. Today is the NFL’s first cutdown day. Saturday is the second. Ross and Barnes will spend the next few days hoping they’ve done enough to make it.

Coates, however, had no illusions about his pro potential.

“I knew that part of my life was over,” he said. “I just had to accept it and move on.”

That, Wolford said, is the first step.

It’s also the biggest one.

“I never tell a guy it’s the end,” Wolford said. “I think maybe that’s crushing their dream and if someone wants to try, I always encourage them. There’s a lot of leagues out there and even though not everybody’s meant to play in the NFL, guys can play in the Arena League or one of the other leagues.

“But, realistically, after you try it once or work out for the pro scouts or whatever and it doesn’t work out, it’s time to take your degree and your education and use it.”

43

43