Federal agency seeks to restart chimp research

MCT

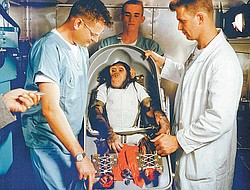

A three-year-old chimpanzee, named Ham, in the biopack couch for the MR-2 suborbital test flight. On January 31, 1961, a Mercury-Redstone launch from Cape Canaveral carried the chimpanzee "Ham" over 640 kilometers down range in an arching trajectory that reached a peak of 254 kilometers above the Earth. The mission was successful and Ham performed his lever-pulling task well in response to the flashing light. NASA used chimpanzees and other primates to test the Mercury Capsule before launching the first American astronaut Alan Shepard in May 1961. The successful flight and recovery confirmed the soundness of the Mercury-Redstone systems.

McClatchy Newspapers

ALAMOGORDO, N.M.

During Lennie’s life under the microscope, science changed.

Starting in the 1960s, Lennie, a chimpanzee, was strapped in a spacesuit for U.S. government test flights and subjected to spinal taps. He was fed a banana laced with triparanol, a drug already removed from the market for humans. In the 1970s, he was a breeder, used to increase the supply of lab chimps. In the 1980s and 1990s, he was infected with the HIV and hepatitis viruses and subjected time and again to blood draws and biopsies.

In 2002, Lennie died at a federal primate facility in the New Mexico desert, where many of his former cage-mates still live.

Today, those former cage-mates — about 180 of them — are at the center of an impassioned debate between the National Institutes of Health and the animal-rights community. The chimps at the Alamogordo Primate Facility have been withheld from research the past 10 years as part of an agreement between the NIH and the Air Force base where the facility is located. Now the NIH wants to move the chimps away from Alamogordo, where they’ll be allowed to be put back into research. Animal-rights activists want them retired to a grassy sanctuary.

Even before Lennie’s death from apparent heart disease, though, science was moving away from the kind of research that dominated much of his life.

Researchers say advances in laboratory techniques mean that knowledge once gained only by examining a live animal now can be learned in a petri dish. And an expanding body of evidence shows that chimps don’t work as the human fill-in that researchers once hoped they would.

The ethics of animal research also has evolved. What once was commonplace is now controversial, and there’s a growing feeling that chimps should be spared the pain and mental anguish of research.

Some see it differently. Calling chimps crucial to advancing hepatitis-C research, the NIH wants to ship them from the facility in New Mexico to the Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio. The director of the Texas institute’s primate facility called chimps “a wonderful model” for certain research.

The use of chimps in research has been a hot-button issue for years. When the NIH said last year that it planned to move the Alamogordo chimps back into research, there was an outcry from advocates and some lawmakers; the NIH announced in January that it will delay any move until an expert panel of outsiders has reassessed its scientific rationale.

In the mid-1980s, scientists who were working to understand HIV and the disease it caused, AIDS, thought chimps would be a vital resource.

Eventually, at least 198 chimps were infected with HIV, according to a 1997 report by the National Research Council, a prestigious body affiliated with the National Academy of Sciences. But just one developed and died from an AIDS-like disease.

The council said chimps could still be of value. But in its report, it concluded that “chimpanzees have not been a universally satisfactory model for human diseases,” and “HIV infection of chimpanzees has not been an ideal model.”

Despite their similarity to humans, chimps don’t react to infection the same way. In HIV research, for example, a possible vaccine protected the chimps but not people, NIH scientists wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2007. Also in 2007, an article in the British Medical Journal concluded: “When it comes to testing HIV vaccines, only humans will do.”

Copyright 2011 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

43

43