Mining knowledge

The Vindicator (Youngstown)

YSU professor Ann Harris said she collects mine-inspection reports from estate sales and auctions. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources also solicits copies of old maps with the location of abandoned mines to add to its archives.

The Vindicator (Youngstown)

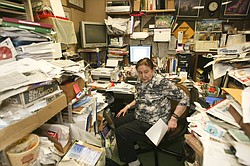

Ann Harris, a Youngstown State University professor, has an office and two storage rooms with stacks of files and drawers full of information about abandoned mines in Ohio and Pennsylvania. She’s working weekly with a university archivist who will make sure the information is properly catalogued and kept.

Geologist Ann Harris documents abandoned mines in the Valley that she’s tracked over 34 years

By Kristine Gill

kgill@vindy.com

YOUNGSTOWN

It was a West Hylda Avenue sinkhole that first piqued Ann Harris’ interest in abandoned mines more than 30 years ago.

The ground below the South Side home weakened in the freeze and thaw season during the spring of 1977, creating a gaping hole where the family’s garage floor once was — unwittingly situated above a mine shaft abandoned around 1917.

“They heard a large noise and a whooshing sound and opened the garage door to find the whole floor of a 20- by 20-foot garage was missing,” said Harris, an emeritus professor of geology at Youngstown State University and certified professional geologist.

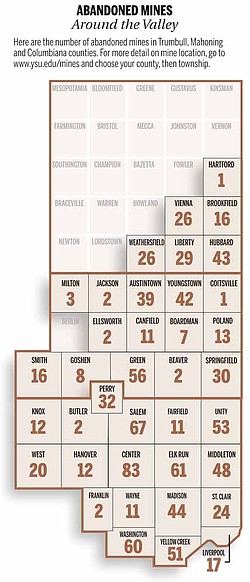

Since then Harris has compiled what is perhaps the most comprehensive mapping of abandoned mines in Mahoning, Trumbull and Columbiana counties. Her website, www.ysu.edu/mines, includes data for most of Ohio and western Pennsylvania.

In 1977, she and other city officials warned residents of risks associated with 260 known abandoned mines in the three-county area. Now Harris estimates that number has grown to more than 1,000 mostly clay and coal mines in eastern Ohio. More than 4,300 abandoned mines have been documented in the state, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

“We’re always adding to it,” Harris said. The walls of her two basement storage rooms and office in YSU’s Moser Hall are lined from floor to ceiling with county histories and mine inspector reports. The stacks of papers and boxes are narrow, and only Harris knows what each contains and where she’s stowed it away.

“I’m not going to live forever,” said Harris, 76. She’s been meeting weekly with University Archivist Ben Blake to assess the information she’s collected and ensure it is preserved.

“I think the great advantage is having her right there to go through the papers” Blake said.

And mapping is important considering problems with subsidence can largely be avoided if a builder or

homeowner is aware of nearby abandoned mines.

“I don’t want these records lost,” Harris said.

Abandoned mines riddle eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania. Lack of regulation in the 1800s resulted in thousands of unmapped sites now blamed for landslides, flooding and sinkholes.

Before 1874, mining operations weren’t reported to the state. Even after laws were enacted to change documentation procedures, mines with fewer than 10 employees did not have to report. Families who mined coal for themselves and their neighbors in the winter and farmed on the land in the summer left behind hundreds of undocumented, potential problems.

“At the time everybody knew who had mines,” Harris said. “But those people move away; those people die; there’s no record.”

Decades later Harris has had to collect most of her knowledge about mine whereabouts through anecdotes and oral histories. She relays that information, sometimes sending copies of maps and data she has on file to homeowners who call her for help. On Tuesday, she had more than six calls to attend to in the busy sinkhole season.

“There’s a lot of snow that’s melting and rain,” said Tim Jackson, emergency program administrator for the Division of Mineral Resources Management’s abandoned mine lands program. “Water percolating through the soil system can cause natural problems and mine subsidence.”

Those factors contributed to a rash of sinkholes in the summer of 1977 following the sunken garage on West Hylda Avenue. Harris would later tend to a sunken swimming pool in Mineral Ridge and a 40-foot wide hole in a backyard on Normandy Drive in Youngstown. In August, a giant hole comparable to the Hylda sinkhole opened in front of Kirkmere Elementary School.

The ODNR maintains a comprehensive database of area mines. Jackson estimates his department receives 50 to 60 complaints of subsidence each year. His department works on half of those projects. After conducting initial testing, they’re revealed to be mine-related.

“A lot of different circumstances can cause subsidence,” Jackson said. “Sewer lines collapse; water lines leak; it could be the collapse of a mine or poor soil.”

Projects are prioritized depending on where the subsidence is located and how much danger it poses. Shallow mines can be filled with stable material and deeper mines are filled mostly with grout. If subsidence has occurred under a home or building, federal funds are available through the Ohio FAIR Plan, which collects a tax from current mine operators. Established in 1968, the Ohio FAIR Plan made all Ohio residents eligible for property insurance.

The ODNR regularly solicits maps from Ohio residents to add to its records. The materials can be donated or loaned. But ODNR can’t afford to contact property owners when mines are discovered near buildings or homes. It’s up to the home or business owner to seek that information.

“Geological survey just returned to me my maps and records they borrowed to scan. I feel better having this information in more than one place,” Harris said.

After all, knowledge prevents major problems when it comes to abandoned mines.

Harris knows. The mine enthusiast stood next to the rig when the abandoned mine in her East Judson Avenue home’s backyard was test drilled. She had a mine map and bought the home knowing what laid beneath. She knew the property’s history. She wasn’t concerned.

“When the word got out that Professor Harris bought a house with a mine shaft and it was OK, a lot more houses sold,” she said.

43

43