Warren official keeps an eye on finances

The Vindicator

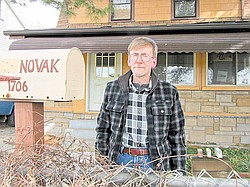

Warren Councilman Al Novak stands in front of his home on Bonnie Brae Avenue Northeast, the house he grew up in and where he has raised his family. He’s been a Warren councilman for 20 years and is finance-committee chairman for a city council with a $26 million general-fund budget. But he earns just more than $20,000 per year stocking shelves at Giant Eagle.

By Ed Runyan

WARREN

The local economy has not been kind to Al Novak, a Warren councilman for 20 years who has worked in the grocery business much of his life.

He made good money and enjoyed a good number of union benefits when the local economy was good. But as the region experienced economic decline, the 57-year-old divorced father of two saw his pay and benefits follow a similar path.

At $11.50 an hour stocking shelves on the midnight shift at Giant Eagle, he made a little more than $20,000 in 2010, plus around $10,000 as councilman.

By contrast, a classmate of his, who grew up one street over from Novak’s home on Bonnie Brae Avenue Northeast, went to work for the city in 1974 and now makes $29.85 per hour. He made $73,000 last year working as project manager in the water-filtration department.

The employee, Rick Griffing, has a Class 2 license, which is two steps below the top license that can be obtained.

“Rick has moved up and moved up, but he’s only moved up because he’s been there a long time,” Novak said of his classmate, who worked toward a college degree but didn’t complete it.

“That’s great that you’ve been around a long time, but in this day and age, we have to have people who are technologically trained. We have to have multitasking people,” said Novak, who has no opponent in the May 3 primary for 2nd Ward council.

In 2010, 427 city employees made $20.5 million — an average of $48,182. On the high end, Capt. Tim Roberts of the police department earned $122,093. Some of that was cashed-in compensation time. On the low end, Atty. Dan Letson earned $854 as a visiting judge.

Novak said his classmate is an example of one of the challenges Warren faces in trying to reduce costs and become more efficient.

Changes in public employment taking place in Columbus will cause veteran city employees to take retirement this year, which makes this a good time to look at ways to reorganize city operations, he said.

As an example, Novak said he thinks it’s likely that the directors of the city’s water-pollution control, garbage collection and wastewater departments will take retirement in the coming years.

Novak said Warren could become more efficient by hiring one individual with the licensing to handle all three jobs.

“There are people looking for a job that are licensed to be a water director, wastewater director; they’re an attorney; they’re a CPA,” he said.

“Every position — when somebody retires — we need to evaluate whether we need that position or not,” Novak said, adding that this would be a big change from the way the city hires personnel now.

Novak has been an advocate for improved efficiency and reducing costs for many years, which is one reason he has pushed on several occasions for the city to adopt a charter form of government. A charter would allow the city to create its own form of government and consolidate positions.

But Novak may be best known for the sacrifices he has expected from himself and fellow city-council members and administrators.

In 2003, council approved Novak-sponsored legislation that took away health-care benefits for council members. In 2009, his legislation froze the pay of council members for 2010 and 2011.

On a personal level, Novak has refused to take cost-of-living increases since about 2005, asking the auditor’s office to deduct $1,000 to $1,400 per year.

And earlier this month, council approved Novak-sponsored legislation that set a four-year (starting in 2012) wage freeze for the mayor, safety-service director, law director and six employees who work under them. It also required those nine employees to contribute 10 percent to the cost of his or her health care for the first time starting in 2012. Most other workers started paying 10 percent of his or her health-care bill in 2010.

Novak said last month’s legislation was needed to show union employees, who have taken pay freezes in the past couple of years, that top officials share in the cost-cutting process.

Mayor Michael O’Brien, who paid back $4,300 of his salary in 2009 and $1,700 in 2010, said Novak understands that city officials need to lead by example.

“With Al Novak, he puts his money where his mouth is or takes money away from where his mouth is, and that speaks volumes,” O’Brien said.

One constituent in Novak’s 2nd Ward, which is between Elm Road and Mahoning Avenue on the city’s north side, is Rick Powell, who owns the Audiax commercial electronics store on Hall Street Northwest and grew up nearby.

“He’s one of the few who will tell you what he thinks, good, bad or indifferent,” Powell said of Novak, adding that most people don’t understand how expensive local government is.

“Most people don’t know the cost. Most people don’t pay attention. As long as it doesn’t affect them, they’re happy. If I have a problem with the street, I call Al. I’ve never had a problem with him,” Powell said.

Though Senate Bill 5 has suggested that the way to cut government spending is to curtail workers’ collective-bargaining rights, Novak said he disagrees with the legislation, in part because the issue probably will get tied up in the courts for a long time.

Novak understands some of the concerns being raised by Gov. John Kasich regarding accrued sick and vacation time for public employees and says cities cannot continue to afford these costs.

In 2009, when former police chief John Mandopoulos retired, he received $118,321 for 960 unused sick hours, 840 unused vacation hours, and 1,117 hours of accrued compensation time. Mandopoulos was paid at his 2009 pay rate — $40.56 per hour.

The city paid around $250,000 in vacation and sick time to retirees in 2010, Novak said.

43

43