Puzzling Problem

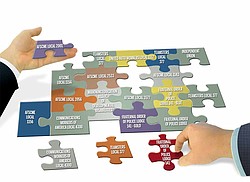

The county has 1,735 employees and 17 labor contracts. Of the 17 bargaining units, six are now engaged in negotiations.

- Senate Bill 5

-

- Referendum leaders turn in petitions to repeal Senate Bill 5

- Kasich to Ohioans: Trust me

- MLK invoked as Ohio union fight moves to cities

- Records: Gov. Kasich resubmitted paperwork

- OHIO’S FISCAL FALLOUT: 10 things to know about SB 5

- Opponents to continue fight against SB 5

- Schools brace for deeper cuts

YOUNGSTOWN

Ohio Senate Bill 5, which would restrict collective-bargaining rights of 350,000 public employees, has added to the uncertainty in Mahoning County’s labor negotiations.

But the new law isn’t the only measure playing a factor in talks with many of the county’s 17 collective-bargaining units.

The cumulative $40 million general-fund shortfall over 10 years of on-again, off-again sales taxes ending in 2005 prevented the county from establishing a rainy-day fund. It also forced the county to borrow more money than would have been necessary, said John A. McNally IV, chairman of the county commissioners, who took office in 2005.

There’s also the local, state and national economy to contend with, and that will make negotiations a little harder.

“We’re also just battling with the past four or five years and the recession across the country that’s also causing us a lot of financial concerns,” McNally said.

Internal issues also are at play.

The county does not have a human resources director to coordinate the county’s side of the bargaining table, perhaps to seek common savings as each deal is worked out. Instead, individual department heads negotiate a deal, normally with the help of an attorney or law firm.

And commissioners fired the Columbus-based Downes, Fishel, Hass and Kim law firm March 10 because county workers complained that the firm was too involved in the creation of SB 5.

On the labor-union side of the bargaining table, there’s pressure, too: Public employees want to complete contract talks before SB 5 takes effect, said Sam Prosser, president of Teamsters Local 377.

“That grandfathers them in,” and protects the negotiated terms for the duration of the contract, he said.

THE BUDGET MESS

The passage of a referendum to make permanent a half-percent sales tax in May 2007 assured the ongoing availability of $14 million annually in revenue to the county’s general fund. In fact, after a salary analysis, hundreds of raises to county workers were awarded; 91 of them exceeded 20 percent or more.

The lush times would be short-lived.

In 2008, every major source of general-fund revenue — sales and property-tax revenue, state funding and investment income — went into in a recession-induced tailspin as unemployment rose in the Mahoning Valley.

Last year, the federal government stopped housing federal prisoners in the county jail, and Youngstown stopped paying for its prisoners. Combined income to the county from prisoners paid for by the federal and city governments fell from $4.31 million in 2008 to $2.96 million in 2009 to $634,900 in 2010.

After 17 consecutive months of decline compared to the same month in the previous year, sales- tax revenues began to recover in April 2010, McNally said. “We’re not out of the woods by any chance, but we’re starting to get a little bit better,” he added.

Now, in the austere budget proposed by Gov. John Kasich, the county faces a loss of $1.2 million in state revenue to its general fund in the state fiscal year that will begin July 1. It could lose between $1.2 million and $2.4 million in the next fiscal year, depending how budget language is interpreted, McNally said.

The general-fund budget for this calendar year is $50.98 million, down 1.4 percent from $51.72 million in 2010.

“We see the erosion of the tax base in terms of ever-increasing foreclosures and vacant properties throughout the county,” McNally said, referring to real estate taxes. Increased unemployment puts a further burden on the tax base, he added.

The impact, however, isn’t limited to the general fund, which is the county’s main operating fund supporting the courts, jail and many other central government functions.

The county engineer’s office saw a $1.5 million revenue loss because of declining income from gasoline taxes and license-plate fees between 2008 and 2009, from which it still hasn’t recovered, said Marilyn Kenner, chief deputy county engineer.

A NEW DIRECTION

Under these circumstances, it’s important for the county to seek every reasonable cost saving it can in labor negotiations, said county Auditor Michael V. Sciortino.

“What you have here is, I think, the great awakening, with the state of the economy, the state of Ohio, with its collective-bargaining issues,” he added.

The county has 1,735 employees and 17 labor contracts. Of the 17 bargaining units, six are engaged in negotiations.

For departments under commissioners’ control, “it would seem to make sense” that personnel policies and labor-negotiation matters be standardized, said Frances Lesser, executive director of the County Auditors’ Association of Ohio.

She added, however, “The commissioners have the budgetary control.”

In fact, the commissioners recently docked the budget of County Prosecutor Paul J. Gains $100,000 after expressing their displeasure with $220,000 in pay raises he gave in varying amounts to all 32 of his assistant prosecutors, who are not unionized.

McNally said he favors a more-unified approach to labor negotiations and to pay and benefits for county employees. He added the administration has a standard set of goals for all county departments in this year’s labor negotiations covering wages, health care, pension contributions and overtime reductions. He declined to disclose them publicly.

McNally noted that coun- ty employees have agreed to major concessions, including unpaid days off, due to recession-induced declines in county revenue.

Many of the county’s labor-union members have been working under terms of long-expired contracts, McNally noted. Looming state-funding cuts are “driving us back to the table” now, he added. “Our goal is not to lay off people. Our goal is to save money,” and provide the best possible services to county residents, he said.

SEEKING HELP

Commissioners are evaluating applications for the human resources director. They received 47 applications for that job by the March 11 deadline, and 18 applicants will be interviewed by commissioners Thursday and Friday.

McNally said he hopes the commissioners can vote by mid-April to hire the new HR director and that the new director can start work by mid-May.

“My first goal right now is to get a highly skilled and competent HR director in here ... so that some of these issues that we’re paying outside folks to do can be done in house,” McNally said. The county’s last HR director, Susan Quimby, resigned May 30, 2009.

Although all county labor-union contracts come before commissioners for approval, the commissioners can’t dictate the salaries paid to nonunion workers in county departments they don’t control, such as the courts, McNally noted.

Also, Ohio law says county commissioners may establish a personnel department, and that any elected official, board or agency of the county may elect to use that department’s facilities and services, but cannot be compelled to do so.

The county also has hired a management-consulting firm to replace the Downes law firm.

McNally said Clemans-Nelson & Associates personnel management consultants of Akron and Columbus will assist the county in labor talks at its Department of Job and Family Services and in the engineer’s and sanitary engineer’s offices.

THE LABOR SIDE

Prosser’s union — Teamsters Local 377 — represents employees of the county treasurer’s office, drivers and mechanics in the county engineer’s office, and supervisors and lawyers in the county’s Child Support Enforcement Agency.

Prosser said labor unions “have to be more united.”

SB 5 is an attack on unions in the public sector, but the effort to weaken unions won’t end there, he said. “It’ll move on to the private sector, and, before you know it, there’ll be no middle class,” Prosser said.

In current negotiations with the engineer’s office, Prosser said his goals are to get eight laid-off Teamsters back to work and to get the bargaining unit under contract before SB 5 takes effect.

Kenner said the county engineer’s department plans no further layoffs this year and would like to have the workers back.

“Our agenda, so to speak, is to work with the union to reduce our costs through [changes in] some of their benefits,” Kenner said.

For example, instead of the current $150 annual cash allowance for boots and $500 for clothing, Kenner said she’ll propose that her office issue uniforms and boots to the employees for an estimated savings of $80,000 to $100,000 a year.

Prosser was noncommittal about the union’s response to that proposal. “That’s all up for negotiations,” he said.

Some of those who used to get the allowance were clerical workers who never left the office.

MORE NEGOTIATIONS

Also in negotiations is the sanitary engineering department, where members of an independent labor union have continued to work under terms of a contract that expired March 31, 2010.

In that office, Bill Coleman, office manager, said a key management goal is “to see how we can incorporate technology in our operations to maximize the performance of the employees.” Coleman said, however, his office is not seeking to use technology to reduce staff.

In the sanitary engineer’s office, John Michaels, union president, blamed the lack of progress in negotiations on what he said was a deliberate stalling strategy by the Downes law firm.

Coleman said, however, the talks were delayed by a study of the office’s finances and that negotiations are expected to resume within the next two weeks with management using Clemans-Nelson.

In the sheriff’s department, the 266-member Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 141, which represents deputies, ranking officers and civilian employees, has a contract expiring June 30, 2013.

Although it is not now negotiating, eight articles in its contract, including wages, promotions and vacations, are subject to reopener at the end of this year.

Sgt. Thomas J. Assion, lodge president, said his union, which has given back though concessions about 27 percent of its pay and benefits since 2008, doesn’t expect to change its approach to negotiations.

“We realize the economic situation of this country, of this state and of the county,” Assion said. He said his goal will be to “negotiate terms that will allow the maximum amount of employees to stay working and to keep the maximum amount of jail-bed space open.”

Currently, 190 of 602 county jail beds are closed, and 48 deputies are laid off.

Retirements and resignations have reduced the sheriff’s staff by an additional 36 people since March 1, 2010, said chief Deputy James Lewandowski. None was replaced, he noted.

THE SB 5 EFFECT

One aspect of SB 5 that Assion finds disturbing is that, under his interpretation of the bill, it would deprive all supervisors, including ranking law-enforcement officers, of all their collective-bargaining rights.

Lodge 141’s gold unit represents sergeants, lieutenants and captains.

“There will likely be a significant number of additional retirements in the rank and the file this calendar year,” due to the changes that would be induced by SB 5 and by other proposed legislation on pension reforms, Lewandowski said.

“Though we perform actions on behalf of management, we do have our own issues that are labor-related,” Assion said of supervisors.

“We have working conditions that we take issue with [such as shift times and training, equipment and staffing levels], and the only place that we’re able to discuss those is at the negotiating table,” Assion added.

McNally said he doesn’t know what impact SB 5 will have before it takes effect — or after. The governor signed the bill into law Thursday.

“I don’t know how that [new law] is going to affect our bargaining long-term because I expect that ... it’s also going to be put on as a referendum,” for a public vote, he said.

43

43