Economy growing without jobs

Associated Press

WASHINGTON

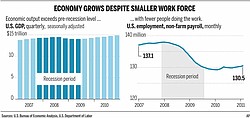

The United States is out of step with the rest of the world’s richest industrialized nations: Its economy is growing faster than theirs but creating far fewer jobs.

The reason is U.S. workers have become so productive that it’s harder for anyone without a job to get one.

Companies are producing and profiting more than when the recession began, despite fewer workers. They’re hiring again, but not fast enough to replace most of the 7.5 million jobs lost since the recession began.

Measured in growth, the American economy has outperformed those of Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Japan — every Group of 7 developed nation except Canada, according to The Associated Press’ new Global Economy Tracker, a quarterly analysis of 22 countries representing more than 80 percent of global output.

Yet the U.S. job market remains the group’s weakest. U.S. employment bottomed and started growing again a year ago, but there are still 5.4 percent fewer American jobs than in December 2007. That’s a much sharper drop than in any other G-7 country. The U.S. had the G-7’s highest unemployment rate as of December.

Canada and Germany actually have added jobs since the recession ended in June 2009.

U.S. companies aren’t acting the way economists had expected them to.

In the past, when the U.S. economy fell into recession, companies typically cut jobs but often kept more than they needed. Some might have felt protective of their staffs. Or they didn’t want to risk losing skilled employees they’d need once business rebounded.

Among manufacturers, for example, some tended to hoard workers during downturns by giving them make-work assignments — sweeping factory floors, counting inventory, painting warehouses.

The result is that productivity — output per workers — has typically decelerated or even dropped as the economy has weakened.

Japan and Europe have been following that script. At the depth of the recession in 2009, productivity shrank 3.7 percent in Japan and 2.2 percent in Europe.

The United States has proved the exception. U.S. productivity growth doubled from 2008 to 2009, then doubled again in 2010, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Panicked by the 2008 financial crisis and deepening recession, U.S. employers cut jobs pitilessly. They slashed an average of 780,000 jobs a month in the January-March quarter of 2009.

Yet after shrinking payrolls, many companies found they could produce just as much with fewer workers. And with that higher productivity came higher profits. By the third quarter of 2010, U.S. corporate earnings were 12 percent more than when the recession began.

By contrast, corporate profits fell 6 percent in Japan and 16 percent in Canada from the fourth quarter of 2007, according to Haver Analytics.

Japanese, European and Canadian companies are less inclined to purge employees. Their customs, labor regulations and unions discourage aggressive layoffs.

U.S. management practices “make it easier for employers to avoid adding permanent jobs,” says economist Erica Groshen, a vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “They have temporary help they can hire easily. They’re less constrained by traditional human-resources practices or by union contracts.”

Fewer than 12 percent of American workers belong to unions, which provide some protection against job cuts. That’s the fourth-lowest union participation rate among 31 countries the OECD tracks.

“When there’s pressure to cut costs in the United States, it’s borne by the workers,” says Howard Rosen, visiting fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “In Europe, it’s borne differently.”

43

43