Calif. panel weighs safety of nuclear power after quake

AP

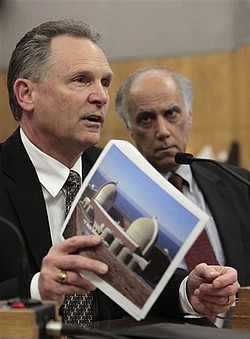

Steve David, director of site services at the Diablo Canyon Power Plant, displays a picture of the nuclear power plant, located near San Luis Obisop, as he discusses the plant's safety in case of an earthquake, during a hearing at the Sacramento, Calif., Monday March 21, 2011. A Senate select committee took testimony from various state agencies, natural gas utilities and the operators of California's nuclear power plants on the state's ability to handle an earthquake and possible tsunami like the one the struck Japan last week. At right is Daniel Hirsch, lecturer in nuclear policy at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Associated Press

SACRAMENTO, Calif.

State lawmakers called on California utilities Monday to delay efforts to re-license nuclear-power plants until the companies complete detailed seismic maps to get a true picture of the risks posed by earthquakes and tsunamis.

State senators raised sharp questions about whether California’s nuclear plants can withstand a major natural disaster such as the one March 11 that has left Japan scrambling to control radiation coming from some of its reactors.

Lawmakers also questioned whether the utilities have been dragging their feet on conducting three-dimensional seismic studies called for in a 2008 state report to assess the risks posed by offshore faults.

Pacific Gas and Electric Co. has applied to renew its license to operate the two reactors at Diablo Canyon Power Plant near San Luis Obispo, which expire in 2024 and 2025.

“I would ask sincerely that PG&E suspend or withdraw that application” until the additional seismic mapping is completed, said Sen. Sam Blakeslee, R-San Luis Obispo, a geophysicist who has been a frequent critic of Diablo Canyon. He said he would pursue legislation to thwart the utility until the mapping is done.

Lloyd Cluff, a seismic expert for PG&E, said work started in October for shallow mapping, and the utility will apply in April for a permit for deep mapping down to 10 kilometers below the surface.

“We’re doing it as we speak,” Cluff said.

Edison has applied to the Public Utilities Commission for permission to charge ratepayers an estimated $21.6 million for similar studies at the San Onofre plant north of San Diego along the Southern California coast, said Caroline McAndrews, director of licensing at the plant.

The license for San Onofre expires in 2022, and Edison has not yet applied to renew it.

California gets about 12 percent of its power from the Diablo Canyon and San Onofre nuclear plants.

Outside the hearing room, Daniel Hirsch, a lecturer in nuclear policy at the University of California, Santa Cruz, noted California’s reactors are in one of the most seismically active areas of the world after Japan. “What’s going on in Japan could happen here,” he said.

Japan’s plants were not designed to handle the ground movement or wave heights they were subjected to this month, said Steve David, director of site services at Diablo Canyon.

Diablo Canyon and San Onofre have been designed to survive much-larger forces, utility representatives testified.

“We’ve gone back this week and verified that [safety] equipment is in place and that the operators have been trained,” David said.

The senators are reviewing whether California’s nuclear-power plants and natural-gas pipelines are safe from earthquakes, as Japan’s crisis raises uncomfortable comparisons to the nuclear plants on the U.S. West Coast.

“Japan has always been a leader in preparedness,” said Sen. Ellen Corbett, a San Leandro Democrat who chairs the Senate Select Committee on Earthquake and Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery

“It’s time to revisit the safety of these plants in light of what we have learned from Japan,” Corbett said.

The utilities contend the plants have been designed and located to protect them from the most serious natural threats considered possible at the sites.

For example, Diablo Canyon is anchored in bedrock and has safety systems and emergency reservoirs located at 80 feet or more above sea level. San Onofre is protected by a 30-foot seawall.

Corbett noted that seismic experts have estimated there is a 2 percent to 3 percent chance of a major earthquake in California each year, and a 46 percent chance of a quake with a magnitude of 7.5 or greater within the next 30 years.

The White House last week asked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to conduct a comprehensive review of safety for all 104 U.S. nuclear plants.

The Union of Concerned Scientists has accused the NRC of lax oversight at some nuclear plants that were subjects of special inspections last year.

At the same time, the Obama administration has been seeking billions of dollars in federal guarantees for the nuclear-energy industry, and nuclear power has seen a resurgence of interest as concerns grow about greenhouse gases emitted by burning hydrocarbons such as coal and oil.

Concerns about seismic safety have haunted California’s two plants for decades as geologists identified new faults near the generators that could produce earthquakes, and safety problems made headlines.

A 2008 NRC report revealed a battery meant to power safety systems at the San Onofre plant, 70 miles southeast of Los Angeles, had not worked for four years.

43

43